Interchange is a burning platform

TLDR

Many fintech business models are based entirely on card payments: they make money when users accept or make card payments.

Startups have been crowding into the slim and inflexible card payment fee pools, although these pools weren’t designed to support multiple venture scale businesses.

Even if these fee pools don’t compress (and there are several growing reasons why they might), startups are starting to realize how limiting interchange alone is.

The smart fintechs that were early to realize these limitations have started to diversify their monetization strategies, providing a few potential models for others.

In 2011, Nokia’s CEO wrote a famous memo comparing the company’s situation to a man standing on a burning oil platform in the middle of the sea.

If the man stays on the platform, he’ll face certain death in the blazing inferno. His only option is to jump into the rough sea and try to survive there.

Nokia faced such a choice in the smartphone market: it couldn’t survive as it was, so only radical product and marketing changes offered a slim chance at survival.

Today many fintechs are built on the “platform” of card payments, generating revenue from interchange and/or acquirer fee pools. These fintechs will face a similarly dire choice as these fee pools shrink and they must adapt or die.

A (big) business can’t live on interchange alone

Interchange – and particularly debit interchange – itself was never meant to support multiple large businesses. Similarly, acquiring is not nearly as lucrative as many think, and especially not with an increasingly crowded fee pool.

There are several reasons why the card payment fee pool may compress, but you don’t need to believe these will change significantly to also believe it’s a bad place to build a business. It’s mainly a question of whether it goes from bad to worse, and if so, how quickly.

This post explores (1) how the card payment platform may become less viable for fintechs, and (2) how smart companies are already adapting their products and business model to respond to these unstable economics.

The brewing storm in card payment fee pools

It’s worth reiterating that even if card fee pools remain as they are today and don’t shrink, they’re still a bad place to build a venture-scale business.

While there are several interesting reasons why these pools might shrink, it’s beyond the scope of this post to explore those in depth. But I want to quickly outline some thoughts, as I’d love reader feedback on these possibilities.

This may sound questionable given that card total payment volume (TPV) has only been up and to the right:

Reflecting this growth, Visa and Mastercard have consistently outperformed the the broader market, as well as fintech and software indexes:

However, most of that incremental volume has been driven by digital channels like ecommerce and software platforms. This would make me uneasy if I were at the helm of Mastercard or Visa. Why? Because card payments were designed for an offline world, and have adapted to work well enough online. Paraphrasing Churchill, card payments are the worst payment method for internet and software, except for all the other ones tried so far. Things could change.

Ecommerce and software platforms recognize the shortcomings of the card payment network, and they have the means and motivation to experiment with alternatives.

Buy-now-pay-later (BNPL) is a recent example of a non-card payment method quickly eating a significant portion of ecommerce volume. Even though consumers’ cards were initially used as the underlying payment method, the rise of BNPL shows two things:

consumers are comfortable with and indeed may prefer non-card payment methods, and

merchants are willing to not only accept non-card payment methods, but also pay a significant premium over card rates for it.

The market for non-card payment methods has been validated to some extent, and there might be more where that came from.

Plenty of other factors could compress card payment fee pools, even if new payment methods don’t. Regulation is a big one. The US allows some of the world’s highest card fees, but these were regulated and capped as recently as 2010 for large banks in the Durbin Amendment. So the US is not adverse to stepping in here and may do so again.

Card payments are a wedge, not a foundation

Whether or not the card payment fee pools compress from here, fintechs trying to subsist on that alone will face the nearly impossible task of building venture-scale businesses from slim and inflexible margins.

Although application layer companies like vertical ERPs and neobanks are most at risk, but infrastructure providers like the payfacs and banking-as-a-service providers are vulnerable as well. Some have recognized this vulnerability for a while and their product strategies reflect this awareness.

So what is the winning strategy? It’s not abandoning card payments entirely. Instead, it’s using the power of sitting in the payment flow as a wedge to upsell complementary higher-margin products—primarily software, value-added services, and lending.

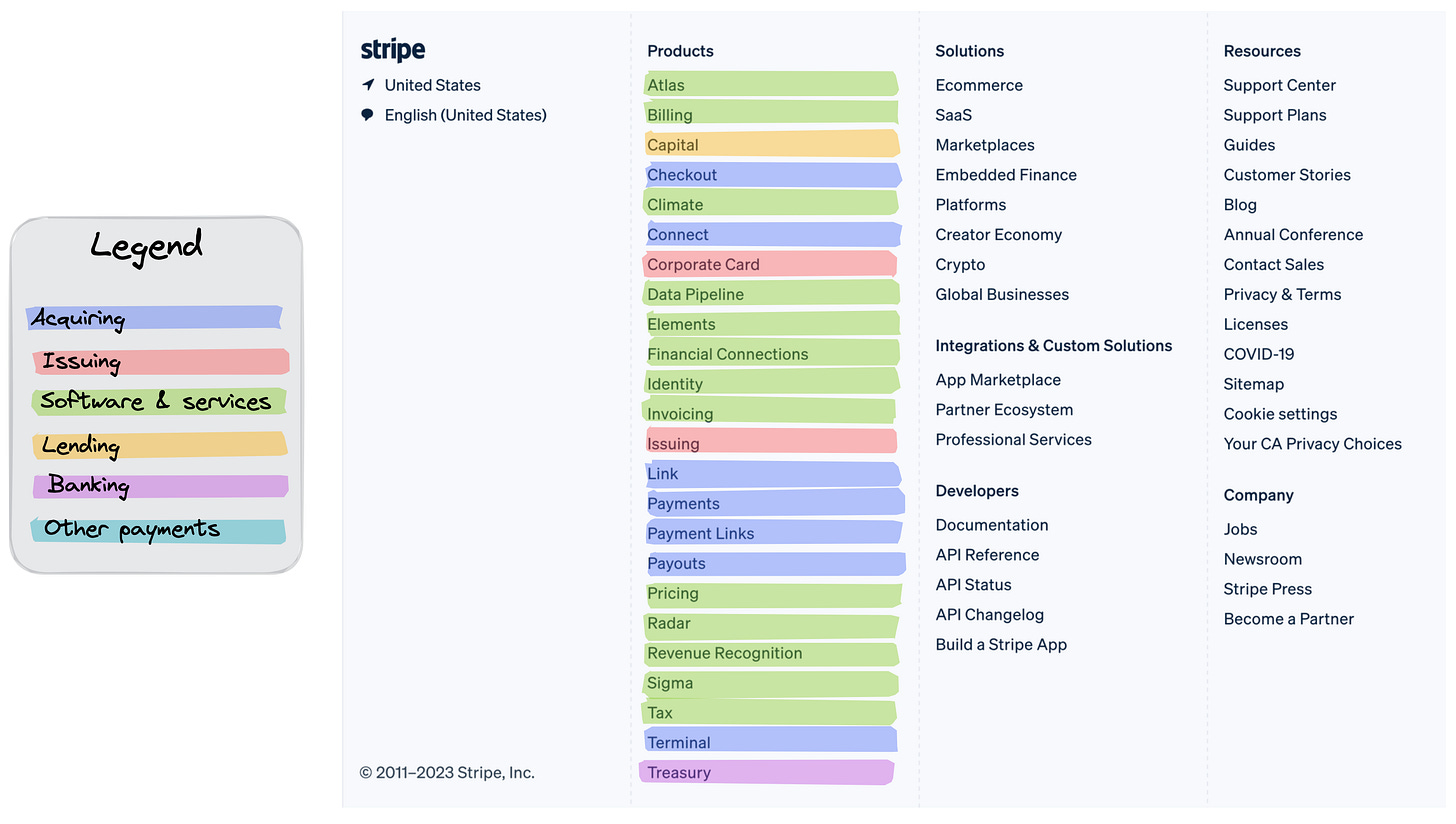

Stripe is a company that’s far along this revenue diversification journey. Over a decade ago it launched Payments and soon after Connect. Starting in 2016, Stripe started launching new products that were adjacent and often complementary to its core acquiring business. These included issuing and corporate cards, variable-fee products tied to acquiring volume (Radar), value-add services (Atlas), lending products (Capital), and more traditional-looking software products (Tax, Billing, Invoicing).

Although the overwhelming majority of Stripe’s revenue still comes from acquiring, color coding their product list by product type shows how much they have invested beyond this core area:

The same split is obvious with their more enterprise-focused competitor, Adyen:

This exercise is illustrative for most mature fintech companies. It’s particularly stark in European neobanks like Revolut, which have much more diversified product suites and revenue streams because interchange is much lower in Europe:

This trend of multi-product, multi-business-model suites is clear across the infra and application layer, as well as across companies that originally depended on issuing and acquiring revenue. Here is Square’s merchant-facing product list:

However, the takeaway from this is NOT “do all the things”. Each company has a slightly different set of ideal customer profiles and core value propositions, so their particular pricing and packaging strategies are different. Some companies may lean more heavily on the software monetization while discounting payments, while others may deliberately underprice the software and payments as a wedge for lending products, and so on.

Vertical ERPs are one example of this trend in the application layer, as vertical SaaS providers are adding payments, lending, issuing, and so on. However, you will also see once “pure fintechs” like neobanks and spend management companies start to build more software and introduce subscription fees.

It’s not just that “every company is becoming a software company” or “every company is becoming a fintech company.” It’s that software companies are becoming fintechs AND fintechs are becoming software companies. Or at least they’ll need to. Expect to see self-described fintechs starting to report their ARR and ostensibley SaaS companies reporting on total payment volume.

The closed loop opportunity opens up

As fintechs discover the limitations of the interchange model, some will go so far as launching their own closed loop payment systems.

Closed loop payment systems have existed in some form for nearly as long as the card payment networks. Gift cards and fuel cards are two common examples. They focus on a narrow payment use case: often the same type of consumer, purchasing the same type of goods, from a specific type of merchant.

These systems don’t need to support the majority of payments for the majority of consumers and merchants. This narrow focus allows these system operators to handle the roles of issuers, networks, and acquirers, and so cut them out of the payment flow and keep premium economics.

In the past it was immensely costly to build the technology and acquire sufficient merchants and consumers to justify closed loop payment systems. However, the cost of building such products has decreased, and the channels and playbooks for acquiring significant user bases have matured. Closed loop payment systems are now a viable strategy for an increasing number of businesses.

That said, it’s still not easy to start a new closed loop payment system. Most of the companies exploring this are already at significant scale and are knitting together large pre-existing merchant and consumer user bases. For example, Square’s Cash App Pay connects Cash App’s ~50M+ consumers and Square’s ~5M+ merchants.

By cutting out the traditional issuer-network-acquirer middleman, Square has the opportunity to more than double its net take rate:

It’s not just consumer businesses that are exploring this. Other platforms that sit atop B2B payments have released some interesting potential precursors to such a network, like Quickbooks’ Business Network and Bill.com’s network payments.

Closing thoughts

Many of the fintechs in the last decade built businesses assuming issuing and/or acquiring would be a sufficiently robust foundation. The seeds of early success for those companies – the self-reinforcing loops of easy VC money and easy fintech infra building blocks – ultimately degraded the already narrow fee pools.

Increased competition and commoditization in fintech applications and infra is causing these companies to scramble for alternative business models. The smartest ones are not dropping card payments entirely, but using them as a wedge for higher margin, stickier, and complementary products like software, lending, and value-added services.

The market is in the early stages of this shift so the playbooks are still being written. The winners will be the ones that can explore, exploit, and scale the right combination of fintech and software as quickly as possible.