VERP Product Strategy: Vertical Software, Payments, and Beyond - Part 3/3

This is the third and final part of a series on vertical ERPs (VERP). Here is Part 1 and Part 2.

Once a VERP owns a key workflow that’s adjacent to payments, it’s in a powerful position to absorb those payments, sit in the business’s flow of funds, and then expand to other financial products. Payments are often the first financial product added, but there are different ways to price it. So, you want to consider the payments pricing strategy in the context of the eventual and full product suite.

How to price embedded payments

Payments have become easier to embed in software products, so they alone are no longer a significant feature differentiator.

There are multiple options to embedded payments, from well-known platforms like Stripe and to payfac specialists like Finix. The right partner for a given VERP depends on the expected payment economics, appetite for risk, and internal resources dedicated to financial products, among other factors. We’ll explore those embedded payment options and trade offs in another article.

However, even a simple payments integration can drive significant user retention. Once your customers are processing payments and have their clients’ payment details stored in your product, it can be difficult to switch to another product.

For this reason, it's often best to keep payments as close to the market rate as possible. However, if you’re a marketplace or are otherwise generating demand for your customers, then you may justify a higher take rate. Tidemark has a great write up on marketplace take rates.

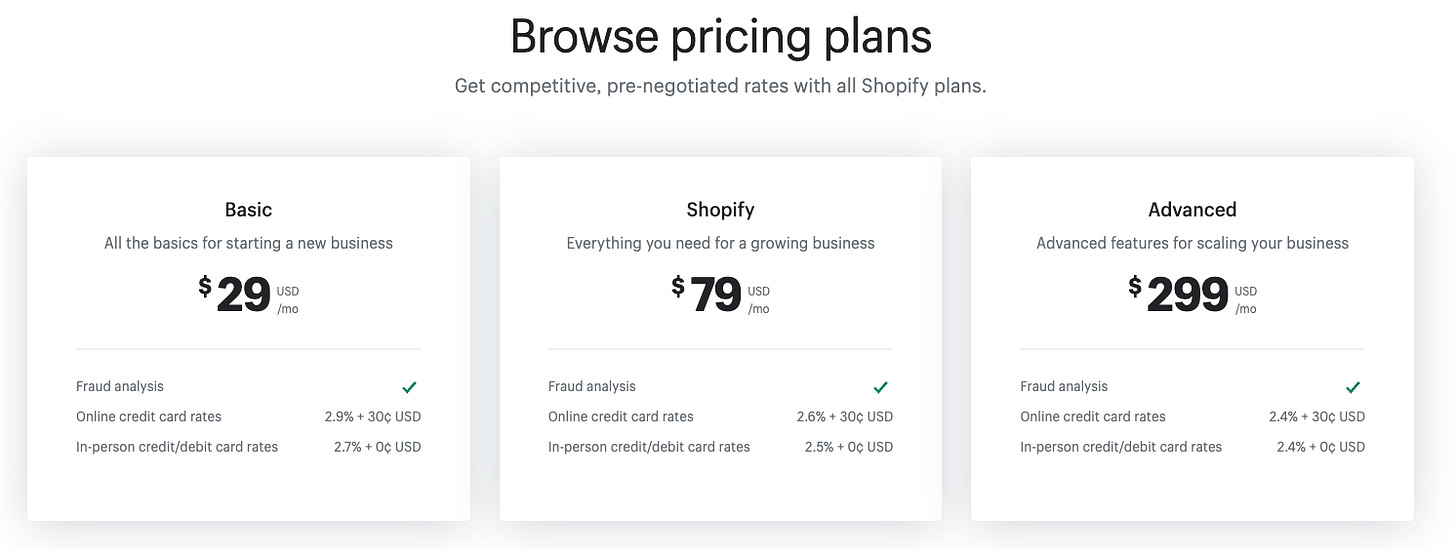

If you’re also charging a SaaS fee, you’ll want to consider whether different SaaS plans will have different payment processing rates. This often comes up later in the lifecycle of a payments program, as you have enough volume to negotiate better pricing with your processor and you have a better idea of the payment volume, risk profiles, and resulting economics of various user buckets. As an example, Shopify lowers its payment processing rates with each higher priced SaaS plan:

You may be able to set up other advanced plans, such as charging higher SaaS fees and/or processing rates for features like storing a client's card and/or subscription billing. Freshbooks does this with its Advanced Payments add-on. Another increasingly popular option is monetizing faster or instant payouts—common in consumer payments apps like Venmo and Square Cash. These typically cost the end user 1-2% of the transfer amount.

However, one of the most important determinants of your payments pricing strategy will be your long-term strategy for other financial products. Payments are a great initial financial product because they are relatively easy to implement and users get value quickly. They’re also powerful because they sit both upstream and downstream of other financial products. If you remember the map from post 2, owning one core business concept or workflow puts you in a powerful position to absorb adjacent ones. So if you’re processing a business’s payments, it is reasonable to offer an embedded checking account to store those funds or a lending product to augment fluctuating income.

Because payments are a powerful precursor to those and other fintech products, pricing payments at or even slightly below market to encourage adoption of payments and other products downstream is often the right move.

Adding other financial products: banking, issuing, lending, and more

Adding financial products beyond payments can be tricky. Products like banking and lending can be great for monetization and retention, but they’re more complex to implement, come with a higher technical and economic overhead, and expose you to greater risks.

Banking, i.e., a deposit account, is a common second addition to a fintech product suite. VERPs will often view deposit accounts primarily as a retention play. With interest rates being what they are and adjacent products like ACH being commoditized, deposit accounts are unlikely to be a big money maker. However, they’re extremely sticky once funded and used consistently.

The payments product becomes key for getting a new account funded. Controlling the funds flow makes it easier to switch its destination to the platform’s deposit account, and having funds stored in that account lowers the risk of fraud and loss from payments.

Issuing a debit or credit card is adjacent to deposit accounts. It’s common to conflate issuing and deposit accounts, since most banking-as-a-service providers offer both deposit accounts and linked debit cards. Like deposit accounts, cards are powerful because once a user develops a habit of using it (i.e., a card becomes “top of wallet”), they’re unlikely to switch to something else. Cards have the added benefit of offering revenue from interchange, or a portion of the spend on the card. This is powerful because it allows the VERP, which also has integrated payments, to effectively double dip on revenue: they take a portion of the incoming payment through their payfac rev share setup, and then a portion of the spend through interchange on the issued card.

Card spending also provides another valuable data feedback loop into the VERP. Expense management is a key part of any business, which is why traditional ERPs provide that data alongside revenue, cash balances, and forecasts. Capturing expense data as well as income data also enables upselling to products like tax prep and even tax filing. This exemplifies the win-win nature of VERP: the VERP monetizes another product that increases platform stickiness, while the end user can save time and not have to chase down data from many different sources to do taxes.

Lending is interesting because a VERP has a wealth of data that traditional lenders don’t. Banks underwrite many different types of businesses without much visibility into or detailed understanding of each business’ unique and underlying operations, but a VERP specializes in a specific type of business as part of its operations. The VERP can see all of the business’ activity: leads, clients, seasonal patterns, outstanding payments, etc. For example, although two businesses may have similar top line revenue in a given month, perhaps one’s revenue is highly concentrated in a small number of customers or much of that revenue is from significantly overdue payments. This more granular data gives the VERP it a significant edge in underwriting.

This data also allows VERP to effectively market lending products to their customers. They know when a business is not only low risk, but also likely to be in need of additional capital. If they have integrated payments, VERPs also sit in the flow of funds and can take repayment through that funds flow, as Stripe and Square do with their respective Capital products. VERPs that know their customers can easily offer products specific to customers’ needs and risk profiles, such as a line of credit vs. merchant cash advance vs. other products like invoice factoring.

However, lending is an incredibly complex product. You need to ensure you have sufficient capital to lend, as well as a robust underwriting model and risk controls, not to mention that your lending products comply with the thicket of regulations around lending. That is all a complex topic for a separate post, but in the meantime, Rohit Mittal has a great series on it.

Wrapping it all up

VERPs offer huge opportunities because they allow startups to absorb much of a business’ workflows and cashflows. This makes VERPs incredibly sticky and offers multiple products and pricing models to maximize monetization, far beyond what’s possible with software alone.

However, covering such widespread functions of a business—from software workflows to integrations to payments and banking—requires a high degree of technical, design, and operational competence across many domains. Thankfully, the rise of embedded fintech options for products like payments, banking, issuing, and lending help to abstract large parts of that complexity of those individual products.

In 10 years, the VERP playbook will be well known and the space more competitive or even somewhat commoditized, as pure SaaS has become over the last 10+ years. But at this moment in time, there are huge opportunities for teams with deep expertise in a given vertical plus a highly entrepreneurial, experimental mindset to discover the playbook to launching and combining these multiple financial and software products.

Hopefully these essays have been a good starting point for thinking about these problems and discovering your own playbook. If you’re thinking about building a company in this space (and have made it to the bottom of the page!), then I’d love to hear from you: mb@matrixpartners.com