Why aren’t there more winner-take-all dynamics in fintech?

This question has bugged me for a while. I don’t have an answer to it, but I have a few hypotheses. I’m publishing this to solicit feedback, so please let me know what you think!

TLDR

The best companies exploit feedback loops like network effects to win in winner-take-all markets.

The financial services market is both uniquely rich with feedback loops and massive in size.

So you might expect there are to be many winner-take-all markets in fintech. But that doesn’t seem to be the case.

Why is that, and what does it mean for fintech founders and investors?

The best companies exploit feedback loops to win in winner-take-all markets

The best founders aspire to build the winner in winner-take-all markets. Paraphrasing Peter Thiel, the best founders build monopolies.

Some markets are more conducive to winner-take-all than others. It seems to me that the more feedback loops exist in a market, the more conducive it is to winner-take-all.

Feedback loops allow a company to exploit some edge to get stronger over time until success begets success. All of the things great entrepreneurs build towards and investors invest in – network effects, economies of scale, virality, etc – are versions of the mighty feedback loop.

The internet and software are rich in feedback loops. That’s why such large businesses have been built in the space and have attracted billions of dollars in venture capital. The startup ecosystem is itself a meta feedback loop… more successful companies and exits lead to more investment chasing the next big thing, which in turn funds the next big thing, and the cycle continues.

Financial services is a massive market with strong feedback loops

First, let’s talk about market size. Coatue pegged the public fintech market cap at roughly $300 billion. That sounds impressive, until you compare it to the $11.1 trillion market cap of legacy financial providers.

Second, financial services is not a market that lacks feedback loops. In fact, nearly every type of loop you can imagine is at play in some or all financial markets.

Money is the original network effect product. The more people trusted and accepted a given currency, the more others used it, and so the more others accepted and used it, and so on. This was as true for stamped coins in ancient Mesopotamia as it is for USD today.

This network effect applies now not only to currencies, but also to payment methods. Consumers want cards from financial institutions that work with Visa and Mastercard because millions of merchants accept those cards. And if I’m a new merchant, I need my acquirer to work with Visa and Mastercard, because it gives me access to those millions of cardholders.

Cost of capital is another powerful feedback loop that spells life or death for many fintechs. Let’s take a simplified example of a lending startup. Because they’re a new and unproven lender, they initially can raise only a small and expensive amount of debt. Then, as they pay their loans back successfully, they can raise new debt facilities that can be both larger and more cost effective. This enables more growth and superior economics than was previously possible, and the cycle continues.

These are just some examples, but there are many other powerful feedback loops in financial services, such as the critical role of trust and brand or the returns to experience in managing risk and fraud.

…but financial services don’t seem to have strong winner-take-all dynamics

Financial services theoretically should have a smaller number of clear winners given its massive size and abundance of feedback loops. (This is just my gut assessment. If you know of a more rigorous method of quantifying the “winner-take-all-ness” of a market, I’d love to learn about it).

It seems straightforward to judge other markets as winner-take-all or winner-take-most. Whether it’s mobile OS share in the US, where the top 2 players own 99.6% of the market:

Or global search volume, where Google owns 85%:

Or ride sharing in the US, where Uber owns 69% of the market and Lyft effectively owns the rest:

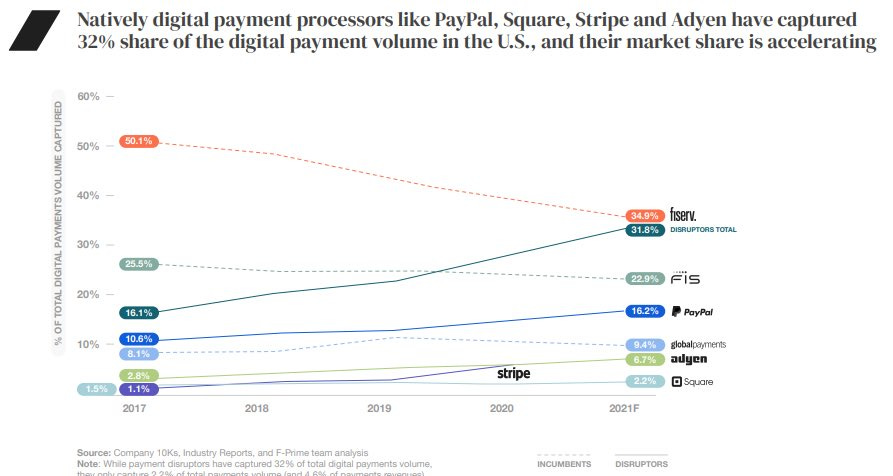

But however you slice the financial services market share – globally or by country, by subsector, by market cap or number of accounts or assets or payment volume, etc – there doesn’t seem to be as much concentration. Here are a couple of graphs showing the rough market shares of different financial service providers.

You get the idea. Whereas other large markets with strong feedback loops have one or two winners with 80 to 99%+ market share, market leaders in financial services don’t often capture more than 10-30%. What gives?

Why are there no winner-take-all dynamics in fintech?

Here are a few hypotheses.

Market structure is a deliberate function of government policy. National governments have a strong point of view on the ideal market structure for their financial services industries. They also have a robust toolkit to enforce that structure. They can grant or revoke licenses and charters, set arbitrary limits on fees, approve or deny acquisitions and mergers, and so on.

Governments may try to strike a balance between limiting the number of financial institutions so they can be adequately monitored, but not limiting them so much that incumbents gain disproportionate power and can take market-harming actions. In other words, the rules of the game in fintech may be deliberately set up to keep the structure from becoming winner-take-all.

Geographic differences further fracture the addressable market. This is tied to the point above. When you multiply “governments wanting not too few and not too many players” with 190+ countries, each of which has their own incentives and regulatory tool kits, you further splinter the potential market.

The market is just so large that it’s impossible for a winner to take all or most. Every person and every business in the world needs to interact with money on a daily basis. So it’s not surprising that financial services has the largest gross profit pool of any market: $6.5 trillion versus healthcare’s $4.8 trillion, ecommerce’s $1.9 trillion, and software’s $700 billion.

We’re defining markets incorrectly: financial services markets are best defined by who they serve, not what they serve. An iPhone or Uber ride or Google Chrome can be equally valuable to a student in San Francisco, a doctor in Denver, or a businessperson in Boston. And while each of those people needs a way to accept, store, invest, and spend money, they each have different needs and risk profiles beyond that, which makes it difficult for them to all be served well by a single financial institution. So perhaps if you define these markets from a bottoms-up, user-segment-first, or jobs-to-be-done perspective they are smaller but are more realistic and cohesive markets, which have much more of a winner-take-all dynamic than would appear from a top-down, overly broad definition of each market.

Understanding market structure is key

It’s important for founders and investors to think about the structure of the market that an early stage company is entering. This structure can be a headwind or tailwind to fast growth and a defensible business. As important, that structure can also act as a ceiling on the size of an individual company even if the TAM is significantly greater.

Successful internet and software companies exploit feedback loops to capture substantial market share in relative terms and build large businesses in absolute terms. Incumbent and modern financial institutions that exploit many of the same feedback loops have built large absolute businesses, but these represent a relatively and surprisingly smaller share of the overall market.

Are fintechs naturally capped at building “large but not winner-take-all” businesses because of something inherent in the financial services market structure, as the legacy institutions have? Or has the market lacked the deflationary power and efficiency gains of software, which are starting to seep into the traditional financial services market via fintech?

Thoughts or questions? Get in touch: mb @ matrixpartners.com

Header photo by Vadim Bogulov on Unsplash