Bundling, unbundling, and timing

The tech industry loves bundling and unbundling. Jim Barksdale’s famous quip from the early 1990s – “There are only two ways I know to make money in business: bundling and unbundling” – is as relevant today as at any point in the last few decades.

There’s been a lot written on how bundling/unbundling works1, but little on when it works. This is critical for founders and investors to understand. Bundling and unbundling are great strategies, but they’re diametrically opposed. So when should founders pursue one or the other?

There seems to be a recent divergence in early stage markets, with many fintechs bundling and many B2B SaaS companies unbundling. This is my attempt to think through why that is, and when bundling or unbundling is the dominant strategy.

It’s about time to bundle or unbundle

Founders often make one of two mistakes with bundling and unbundling. Some just do the opposite of whatever most of the market is currently doing. For example, in a market dominated by bundles, the correct strategy is not necessarily to unbundle. Other founders simply copy the dominant strategy and build the Nth bundled or unbundled product—but that’s also not necessarily right. Both approaches are a quick path to mediocrity because they ignore market conditions.

Two factors determine whether a market is more amenable to bundling or unbundling:

Demand-side buyer preference. What are buyers optimizing for: cost or quality?

Supply-side tech changes. Is there some new tech or other change, like a new business model or regulatory regime, that enables a new product and/or makes it cheaper, more accessible, or easier to distribute?

When one or both of these change, it creates a narrow window when a new strategy (bundling or unbundling) becomes dominant before many realize it. Founders who recognize these shifts and act on the newly-dominant strategy while the market is still pursuing the opposite one have a significant edge. Let’s discuss each pattern in more detail.

Buyer preference determines bundle preference

Buyers generally face tradeoffs between cost and quality. This is more of a spectrum than a binary choice. They can spend more to get exactly what they want, or spend less on something “good enough.”

In the image below, think of “completeness of solution” as “how many things a product does,” and “depth of solution” as “how well it does the thing(s).”

It may help to look through the lens of bundled cable versus unbundled streaming services. Basic cable includes several different entertainment options: some news, some sports, some TV shows and movies. That’s probably good enough if you don’t care too much about what you watch.

But if you have kids, you’ll likely pay extra for Disney+’s deep catalog of children’s shows. If you love documentaries, you’ll want a subscription to Curiosity Stream. If you’re a sports fan, you’ll probably pay for ESPN+.

You can think of Curiosity Stream as having way more depth in documentaries, but limited breadth beyond that. Basic cable may have some documentaries from time to time, but they’re unlikely to have the same quality and quantity as an unbundled product like Curiosity Stream.

Economic conditions are a big factor in whether a buyer optimizes more for cost or completeness. In good times, buyers have more spending power. So, they’ll generally optimize for quality of outputs rather than costs of inputs. A company might buy and integrate several best-of-breed point solutions rather than a single integrated suite, or a consumer might subscribe to multiple streaming services. Unbundling has an edge in these conditions.

The opposite is true of weaker economic times, when buyers focus on cost and satisfice with a product that does “enough well enough.” This gives an edge to bundles. Total cost of ownership is important here. For example, in the B2B example, if a company is reducing headcount, it’s more economical to have fewer tools that the core team is proficient in, rather than many specialist tools (and specialist headcount to manage them).

Just as the economy goes through cycles, the relative opportunity to bundle or unbundle cycles back and forth. Founders who recognize a shift can pursue the newly dominant strategy for months, or even years, before the rest of the market adapts.

New tech catalyzes unbundling

New tech allows startups to use unbundling as an offensive strategy. All else being equal, newer companies are more likely to adopt new tech than older ones. This allows them to create narrower, superior products as unbundled point solutions to wedge into a market.

The emergence of SaaS in the late 1990s and early 2000s was one such tech shift that catalyzed waves of unbundling across industries. It allowed new products to be built, sold, and maintained much more cheaply than on-premise software. SaaS also supported novel distribution strategies—free trials and freemium, self-service, recurring billing. This allowed startups to unbundle the incumbents with point solutions that were superior to on-premise bundles.

Salesforce exemplified that shift. The founder Marc Benioff spent his early career at Oracle, a company known as an aggressive bundler. CRM was a classic part of the enterprise software bundle built by incumbents like Oracle. Benioff launched Salesforce as an unbundled CRM with the cost, quality, and distribution advantages of SaaS.

The catalyst for unbundling can be more than software. New business models and regulatory regimes evolve symbiotically with new tech to create unbundling opportunities. A few recent examples in fintech include everything from payment facilitator (payfac) models, to the payment-for-order-flow model that Robinhood used to offer fee-free trading, to the emergence of sponsor bank and banking-as-a-service (BaaS) models.

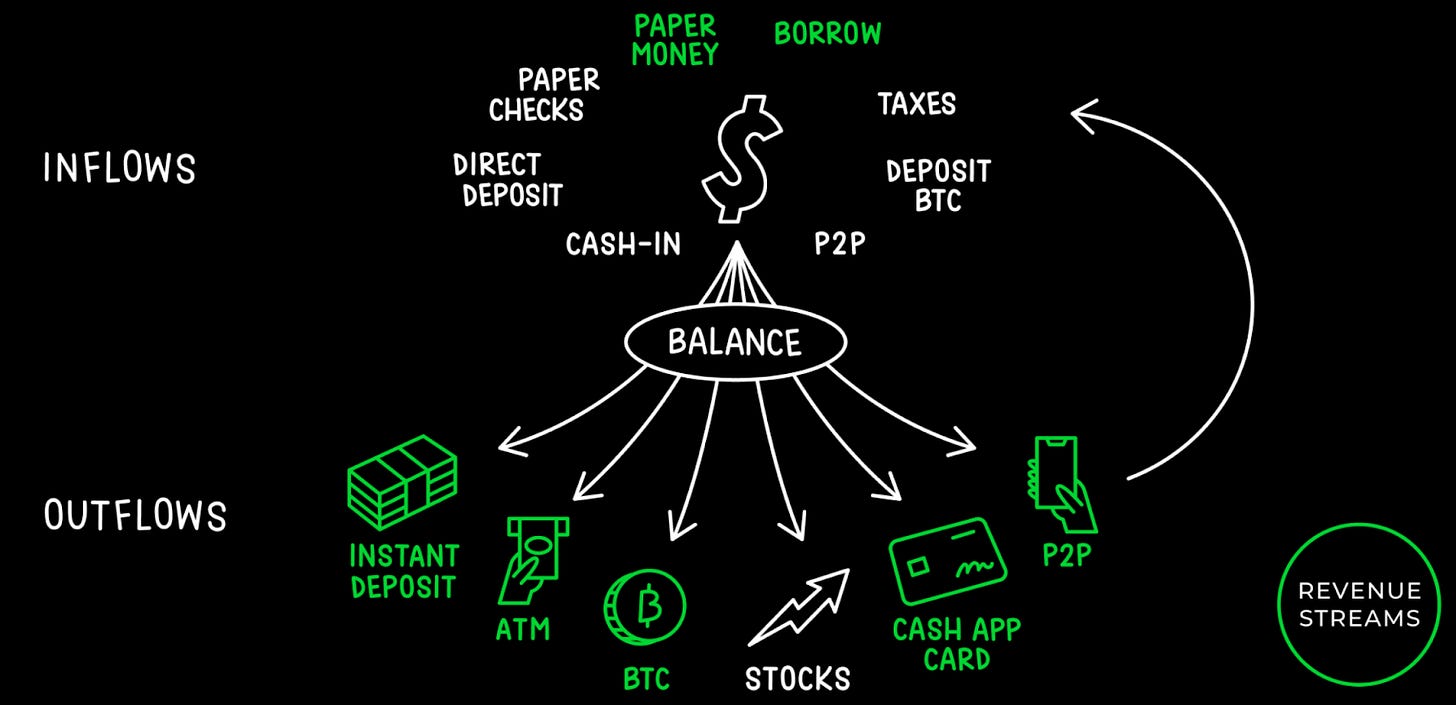

On the fintech side, neobanks are a recent example of this “new tech = unbundling” dynamic. The confluence of several new technologies – mobile phones, sponsor banks and BaaS, consumer ads platforms – allowed neobanks to unbundle checking accounts and debit cards from the traditional bank “bundle” of broader financial services and physical branches.

The neobanks that used this unbundled product as a wedge to acquire users are now aggressively rebundling. As surprising as that may seem at first, there’s a powerful logic to successful unbundlers eventually pursuing the opposite strategy.

If unbundlers survive, they become bundlers

While unbundling is a great offensive strategy for startups, bundling is a defensive strategy for incumbents (or aspiring incumbents).

Demand-side factors are relevant here. If buyer preference shifts from completeness to cost, companies will respond by bundling. Bundling is also a powerful defensive strategy for companies at scale to consolidate and protect market share. It can help increase product stickiness, improve margins or revenue per user, and/or open new customer acquisition channels.

Salesforce today is the cloud version of the on premise bundles it fought against 20 years ago, with an array of products in marketing, ecommerce, customer support, and more.

Neobanks and many other 2010s fintechs are also aggressively bundling. The product pages of most large consumer fintechs are now closer to the traditional financial institutions than their original offerings.

There’s a half life to the power of new tech to enable unbundling. Eventually a sector absorbs and becomes saturated by the new tech. For example, using SaaS to build a compelling unbundled product was a powerful edge a decade ago, but SaaS alone is table stakes today. As new tech saturates a market, it’s more likely to enable bundling and defensive consolidation rather than unbundling.

So, just as timing on the demand-side plays a key role in bundling/unbundling success, so does the timing of new tech on the supply-side going from novel to table stakes determine its efficacy. These cycles determine the dominant strategy at a given time.

Wrapping it all up

Bundling and unbundling are powerful strategies when used at the right time. Founders that recognize the shifts that give a temporary edge to one strategy or another can have a significant advantage in capturing a market.

When evaluating these shifts, the layout of strategies looks like this:

The most powerful time for startups is when the emergence of a new tech coincides with buyers’ preference shift to quality. This provides startups with the means to create a compelling unbundled product as well as a market uniquely receptive to it.

On the other hand, when there is no significant tech change and/or no strong buyer preference shift, there isn’t a compelling reason to bundle or unbundle. Companies can pursue those strategies, but they’re unlikely to provide a significant advantage.

So where is the market today? It seems that fintech is in a strong bundling phase. Not only are buyers optimizing for lower cost, but much of the key new tech and infra in fintech from the last decade is in the later stages of deployment and saturation.

Generative AI seems to be breathing new life into the B2B SaaS market, providing opportunities for startups to unbundle applications across customer support, marketing, HR, and more. This is potentially such a significant shift that incumbents are paying attention too, with nearly every classic software suite touting some kind of AI feature, from Microsoft to Adobe to Salesforce.

The key to bundling or unbundling successfully is timing, timing, and timing. Startups are fundamentally risky and rough endeavors. As a founder it’s worth pursuing every edge, however small, that can increase the chance and magnitude of success. Properly reading market shifts and applying the right bundling or unbundling strategy can provide such an edge. Conversely, misreading shifts and applying the wrong strategy at the wrong time will hamper even great teams in great markets.

The best founders are not only students of their customers and technology, but also of the market’s history and their place in it. Timing matters!

Some good resources out there on this strategy are:

https://cdixon.org/2012/07/08/how-bundling-benefits-sellers-and-buyers