Vertical software already won the context graph

Everyone is arguing about who will build the trillion dollar context graph. The most valuable ones already exist inside vertical software.

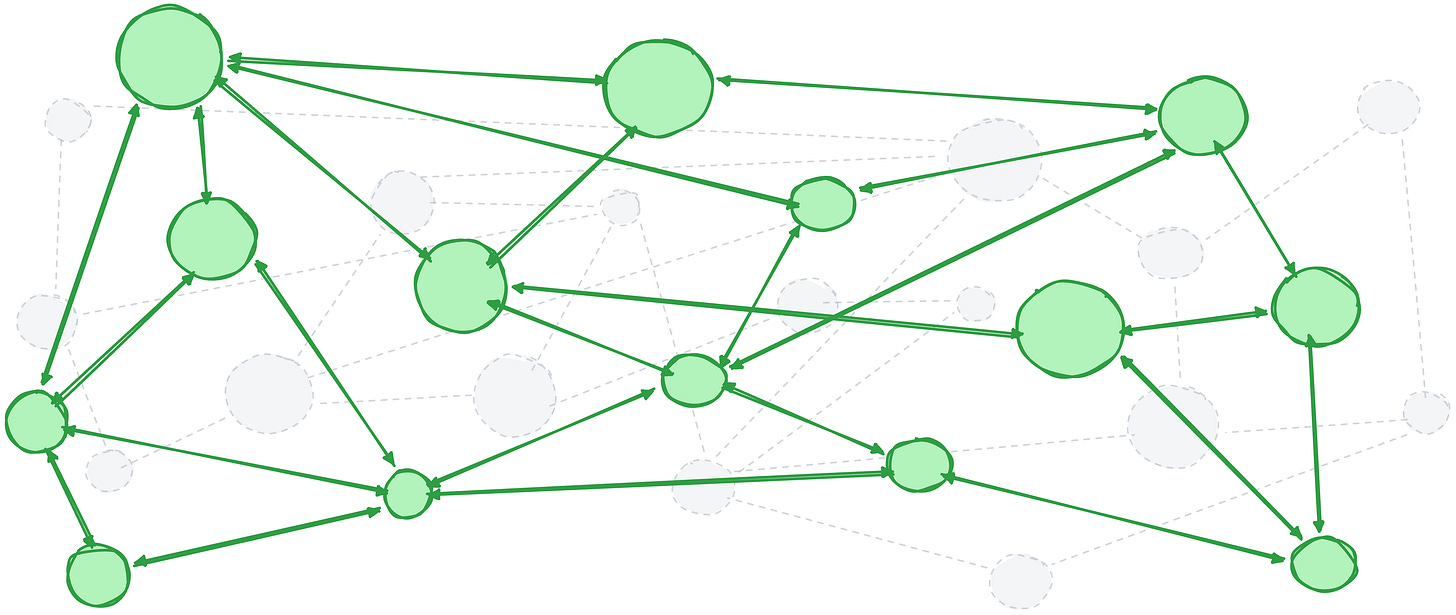

Context graphs have become the new battleground in enterprise software. @JayaGup10 and @ashugarg argued that the next trillion-dollar platform opportunity isn’t in systems of record. It’s in capturing the decision traces that systems of record miss. That’s true, but it’s missing the key point that vertical software companies have been building these context graphs for over a decade.

What’s a context graph & why does it matter for agents?

A context graph is a queryable record of business logic: the reasoning, precedents, and decision traces that explain why things happened, not just what happened. Every company has one in theory. It’s the accumulated knowledge of how the business operates: the exceptions that get approved, the precedents that govern decisions, the tribal knowledge in people’s heads.

Agents need this to move from automation to autonomy. An agent can run a workflow, but it can’t handle exceptions or apply precedent without access to the reasoning behind past decisions. The context graph separates an agent that follows rules from one that exercises judgment.

In most companies and products, the context graph exists in theory but not in practice. It’s scattered, implicit, and inaccessible because:

No one logs the reasoning behind decisions. The VP approved the exception on a Zoom call but never recorded why.

Systems capture outcomes, not context. The CRM shows the final discount, not the service outages or churn threat behind it.

What context exists is siloed. It’s scattered across tools that don’t share a worldview.

These aren’t product bugs. They’re structural features of horizontal SaaS. Generic platforms use flexible abstractions that can model any business, which means they model no business precisely. Humans must bridge the gap between “what the system captures” and “how decisions get made.” But humans don’t leave audit trails.

The trillion-dollar question: who fixes this? The prevailing thesis is that agent startups have a structural advantage. They sit in the execution path at decision time, so they can capture context that systems of record never see. The assumption is that the context graph needs to be built from scratch. But that’s not entirely true.

Vertical software has been quietly building context graphs for decades

The debate has a blind spot: it focuses entirely on horizontal enterprise software.

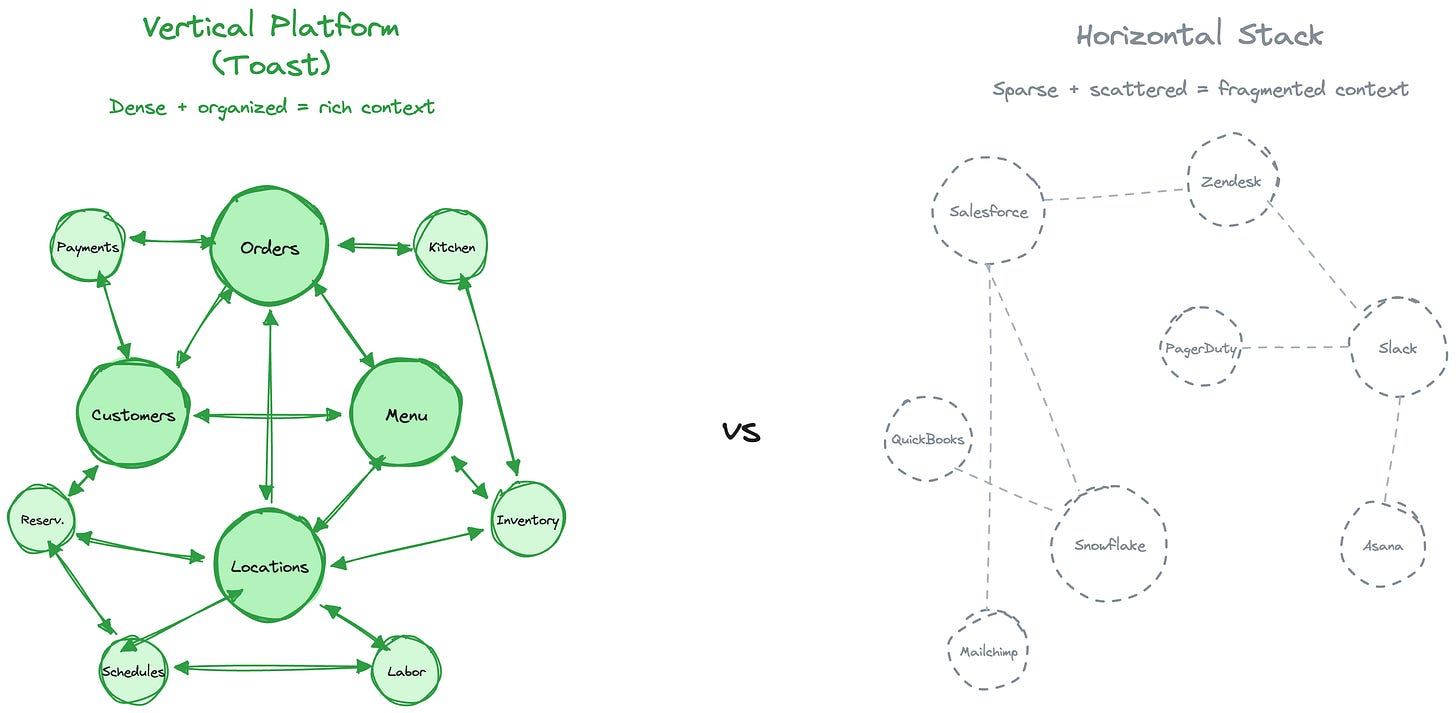

Think about the workflows and software stack of a typical company. It’s a patchwork of horizontal tools, each built for a broad use case, and none designed to really work together. Sure they have APIs and integrations, but even the best integrations drop tons of context as data and actions move through them. The context graph fragments because the tools don’t share a worldview.

But vertical software is different. The difference starts with something I’ve written about before: the data model.

Horizontal platforms like Salesforce use generic abstractions (”accounts,” “contacts,” “opportunities”) that can model almost any business. That flexibility helps breadth but hurts depth. The ontology doesn’t map to how any particular industry works. It’s a blank canvas customers must configure into meaning.

Vertical software starts from the opposite premise. The data model isn’t flexible. It’s opinionated, purpose-built, and mapped to that industry’s reality.

Look at Toast’s data model. You’ll see objects like Order, MenuItem, Customer, PrepStation, etc. These aren’t generic transactions dressed up with custom fields. They’re first-class entities with built-in relationships: orders connect to customers, menu items, locations, and payments as native concepts. The ontology is the domain.

Compare that to Salesforce’s data model: Account, Opportunity, Lead, Contact, etc. Powerful abstractions, but they describe a law firm, restaurant, or rocket manufacturer equally well. They describe none of them well. Configuration, integrations, and human memory must bridge the gap.

Opinionated data models bootstrap context graphs

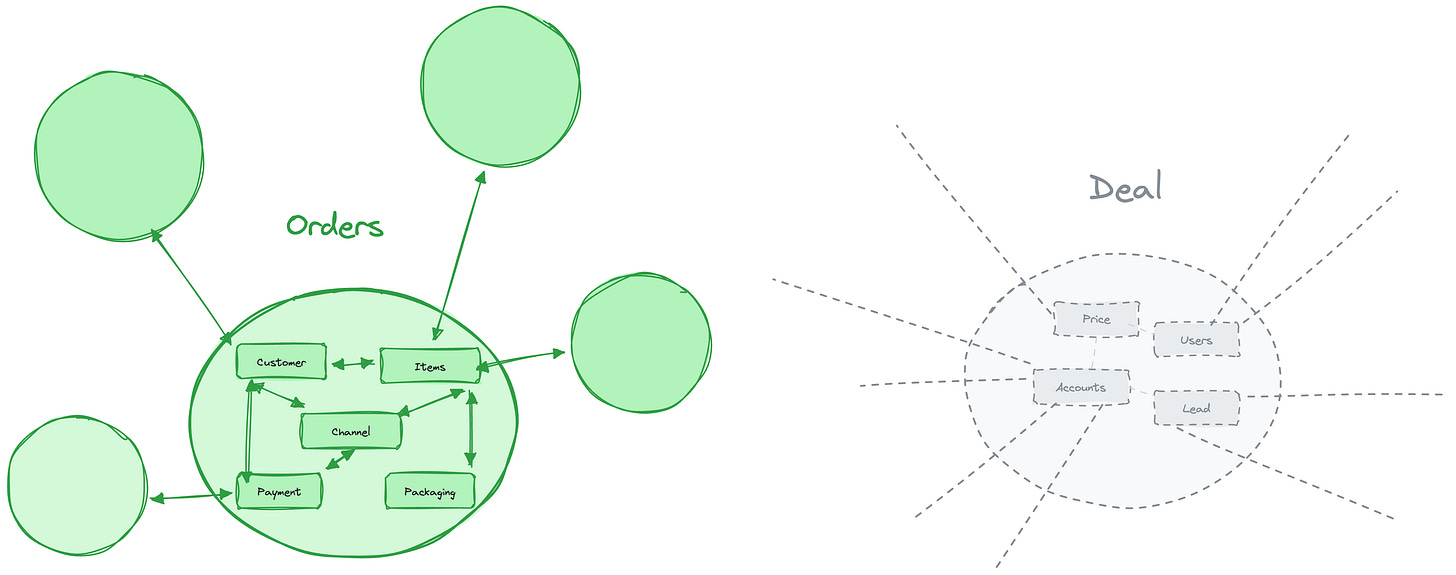

In vertical software:

The reasoning gets recorded because the system is built around actual business decisions. When a construction platform tracks change orders, it captures why the change happened (weather delay, subcontractor default, scope change) as structured data, not notes in a generic “activity” field.

The context isn’t siloed because vertical platforms consolidate functions into one system. The construction platform isn’t just project management; it’s also scheduling, procurement, billing, and field operations. One system, one data model, one view of reality.

The full decision trace is reconstructible because the ontology supports it. When everything from estimate to invoice lives in a system built around menu items or job sites or patient treatments, you can trace how a price changed, why a timeline slipped, or what drove a discount.

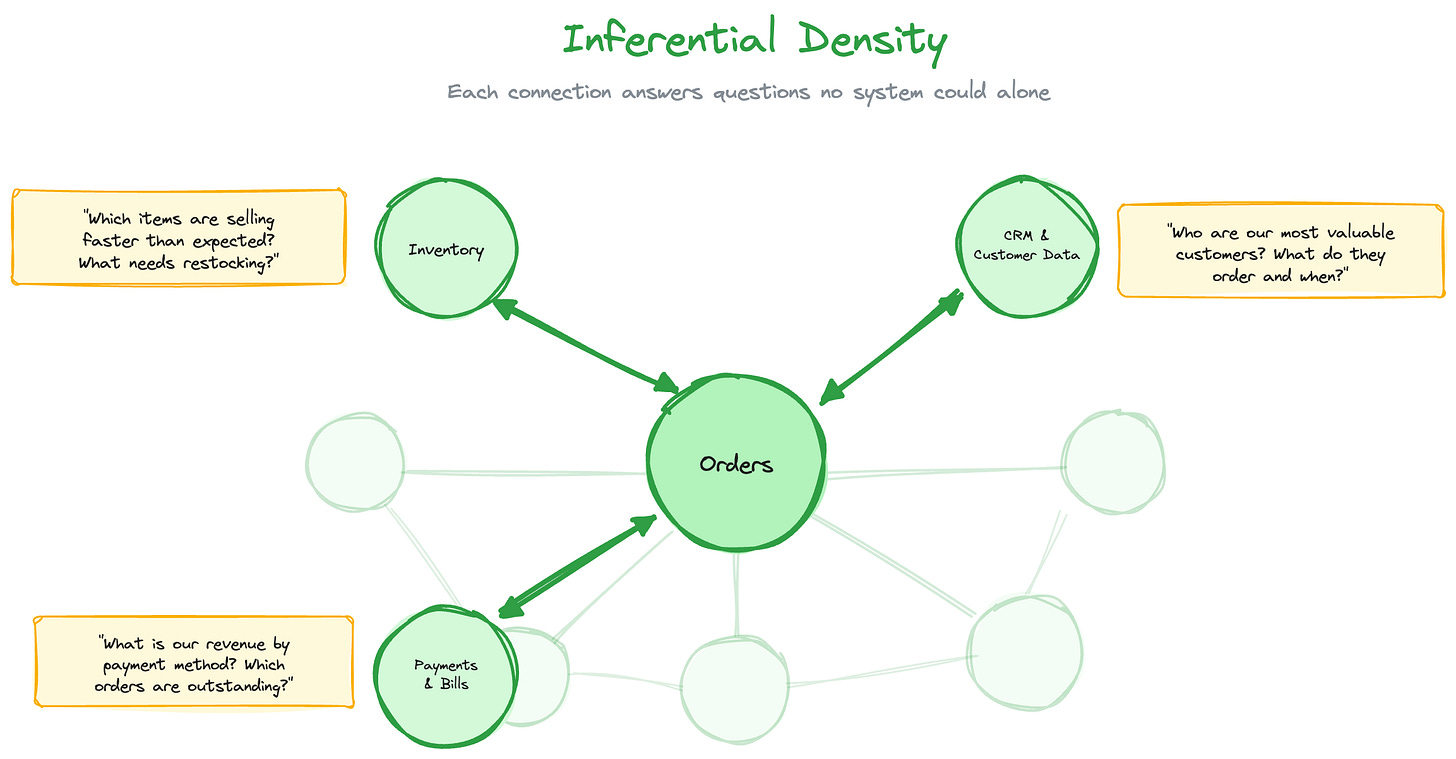

Inferential density: a different way to capture “why”

There’s a deeper point about how context graphs work. The original context graph thesis assumes decision traces need explicit capture: an agent logs “I did X because of Y” at the moment of decision. But there’s another way the “why” becomes accessible: through inferential density. When the graph is sufficiently rich, the reasoning can be reconstructed from relationships between nodes.

Consider an order in Toast. Alone, it’s just a transaction with attributes. Connect it to inventory and you know which items are selling faster than expected and what needs restocking. Connect it to customer data and you know who your most valuable customers are, what they order, and when. Connect it to payments and you know revenue by payment method and which orders are outstanding.

Now when you see a spike in refunds, you don’t need someone to log what went wrong. You can see that the spike correlates with a specific menu item, the inventory system shows that ingredient was substituted due to a stockout, and the affected customers skew toward your highest-value segment. The reasoning is embedded in the relationships.

Each new function adds inferential power to everything already in the graph. Inventory data makes orders more meaningful. Customer data makes inventory decisions more meaningful. Payment data makes customer relationships more meaningful. The context graph doesn’t just get wider; it gets denser. Density makes the “why” reconstructible without explicit capture.

This is the structural advantage vertical platforms carry into the age of agents.

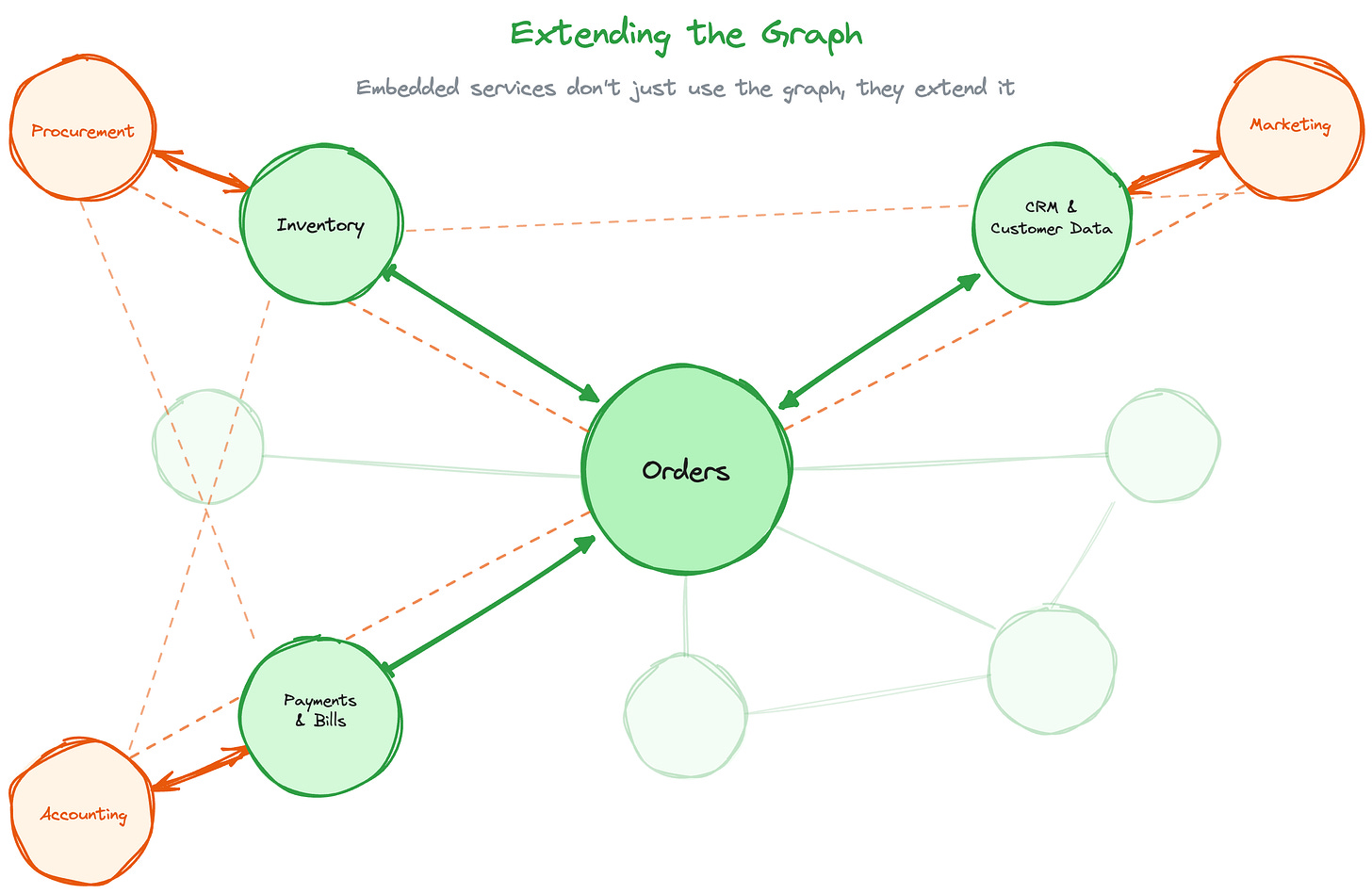

How vertical software is extending the context graph at the edges

Vertical software companies didn’t build these context graphs by accident. They were forced to go deep because they couldn’t go broad. A construction platform or dental practice system faces a ceiling: there are only so many construction companies, only so many dental practices. If you can’t grow by adding customers across industries, you grow by capturing more value from each customer within your industry.

Embedded payments was the proof point. When a vertical platform embeds payments, such as with Rainforest, it isn’t just adding a monetization layer. It’s extending the context graph into new categories. The platform knows not just what transactions happened, but the full economic reality: payment velocity, cash flow patterns, default rates. Every transaction adds to the accumulated knowledge.

The same logic now drives the next wave. Vertical platforms have spent a decade consolidating the operational core. But activity at the edges (customer acquisition, purchasing, workforce management) still happens outside the platform. Marketing in Mailchimp. Procurement in email threads. Accounting in QuickBooks. Each represents a gap in the graph.

Why vertical platforms can now absorb more edge functions

The foundation exists. Vertical platforms have domain-specific ontologies, core operational modules, and deep customer relationships. They understand what a job site is, what a patient treatment plan looks like, what a menu item costs. This is the precise business logic edge functions need to plug into.

The financial layer is in place. Embedded payments gave vertical platforms visibility into the money moving through their customers’ businesses. That financial context is essential for procurement and accounting, which live at the intersection of operations and money.

AI changes the economics. Marketing, procurement, and bookkeeping require labor. They’re judgment-intensive and context-dependent. AI can now handle workflows that previously required humans. The vertical platform, with its deep context graph, is the ideal substrate.

A few categories we’re tracking here:

Marketing pulls customer acquisition into the graph. Reach routes customer communications and other marketing data through the vertical platform itself, connecting acquisition cost to the customers it produced.

Accounting pulls financial categorization into the graph. With Layer or Tight, transactions get categorized within the platform rather than exported to QuickBooks, closing the loop between operations and the books.

Procurement pulls purchasing into the graph. Companies like Sticker and Faliam bring supplier relationships out of email threads and into the system of record, making spend visible alongside operations.

Each follows the same pattern: absorb an adjacent function, blend context with financial data, deploy AI, and deepen the graph.

So what?

Horizontal SaaS will lose ground. These companies have brand equity, data gravity, and deep workflow integration. But they’ll lose share to agent-first startups smart about bootstrapping context graphs, and to vertical incumbents picking off customers tired of stitching together horizontal solutions.

Agent-first startups face a cold start problem. The context graph thesis is right that agents can capture decision traces. But vertical software already owns the workflow for millions of businesses. An agent startup building for restaurants competes with Toast’s distribution, data, and decade of accumulated context. A hard gap to close.

Vertical software incumbents are undervalued. The market prices vertical software on revenue and growth. It doesn’t price the context graph. As horizontal SaaS struggles and agent startups face distribution challenges, vertical platforms with dense context graphs have a structural advantage the market undervalues.

Embedded service providers are an emerging category worth watching. Not every vertical platform will build the graph extensions in house. Embedded solutions will be more attractive. marketing, procurement, and accounting in-house. Their growth is complementary to vertical software’s expansion. As vertical platforms absorb more functions, the infrastructure providers that enable it become more valuable.

The trillion-dollar context graph opportunity is real. But it won’t be captured by whoever builds the best agent. It will be captured by whoever already has the deepest graph and knows how to extend it.

My name is Matt Brown. I’m a partner at Matrix, where I invest in and help early-stage fintech and vertical software startups. Matrix is an early-stage VC that leads pre-seed to Series As from an $800M fund across AI, developer tools and infra, fintech, B2B software, healthcare, and more. If you’re building something interesting in fintech or vertical software, I’d love to chat: mb@matrix.vc