Price and shape risk that others can't or won't

Why the canonical startup advice of "make something people want" doesn't apply to fintechs, who are ultimately in the business of pricing risk and "selling money".

Of the many light-hearted digs at fintech, this is one of my favorites:

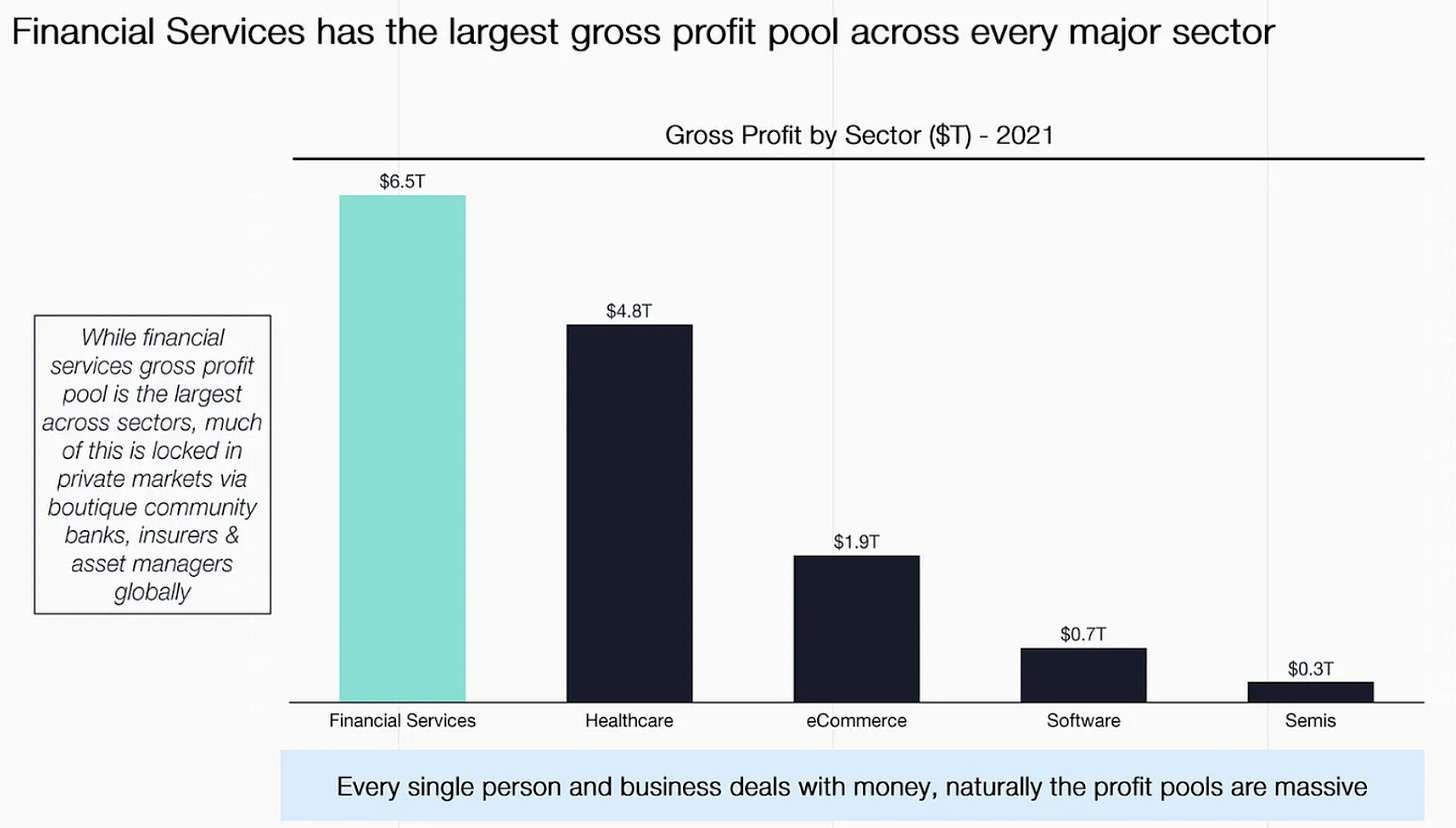

It’s a tweet I quote often. On the one hand, financial services is one of the largest, oldest, most efficient, and most competitive markets. Incumbents have immense competitive advantages. There is a lot of money left on the table. Financial services has the largest gross profit pool of any sector, almost 10x the entire software industry:

On the other, fintechs are some of the largest and fastest-growing companies.

How do you reconcile the two realities? More importantly, why do so many fintech founders run headlong into a brick wall attempting to win those profits? It’s because they mistakenly believe they’re selling a product or service, when in fact they’re selling money. Understanding this distinction is the difference between success and failure.

It’s easy to make something people want… when you’re selling money

YC knows a thing or two about building valuable companies. They’ve funded 5,000 companies worth >$600 billion, including 900+ worth >$100M and 90+ worth >$1 billion.

YC’s motto is “make something people want”. They print it on posters and t-shirts, and mention it three times on their homepage:

Most (non-fintech) startups fail because they build something that no one wants (market risk). Others fail because even though people want what they’re building, they can’t build it (technical risk). So, working backwards from “something people want” is great advice for most startups.

However, “make something people want” is incomplete at best and dangerous at worst for fintechs, because much of financial services involves selling money (or access to it). If most other startups need to think about market risk and/or technical risk, most fintech startups need to think about “risk risk”. Payments infrastructure allows for money to be sent and received. Banking for it to be stored. Lending for it to be borrowed. Investing for it to grow. Insurance for it to be protected. All of these activities involve real downside risk unique to financial services: bad actors can process fraudulent payments, borrowers can not repay loans, and policyholders can make more and greater insurance claims than expected. There are innumerable ways to lose money.

Traditional financial services is so big and profitable because it’s good at selling money… but more importantly, at getting it back. Selling money is easy. Getting paid back is difficult. It’s about understanding and pricing risk.

Many fintechs mistakenly just focus on the “selling” part. They often have clever approaches that make it easier to sell money, but don’t much improve the likelihood of it getting paid back.

So, the motto for fintechs isn’t “Make something people want”. It’s not even “Get good at selling money” or “build a great product” or “be great at user acquisition”. All of those are necessary but not sufficient. The wordy but correct motto for fintechs should be “Price and shape risk that others can’t or won’t”.

“Price risk” means deciding which customers to serve and what terms to offer them. Terms vary by product, but simple examples include the interest rate and duration in lending or the required reserves and settlement timing in payments.

“Shape risk” is what you do after you’ve sold a product to increase the odds of getting paid back. This also varies widely, but can include a bank providing tools or education to help its business customers grow and expand, or a lender sitting in a funds flow, such as a payment processor or payroll provider, to ensure they’re paid back first.

“That others can’t or won’t” is the critical part of the motto. That’s because traditional financial institutions are pretty good at pricing and shaping risk for most customers and most products. They often excel in acquiring the most attractive customers (high value, low risk) and then pricing and shaping risk to sell them financial products profitably. The shortcomings of traditional financial service product surfaces (mobile apps, websites, customer support) are a big red herring, as those often have minimal bearing on what matters: evaluating the risk needed to sell money.

This is the result of significant advantages in brand trust and marketing spend, historical data and processes to underwrite, and more. So the deck is heavily stacked against challenger fintechs. The way to win this brutal game of “selling money” is not simply to take more risk, but to take different and smarter risk.

How to lose money selling money

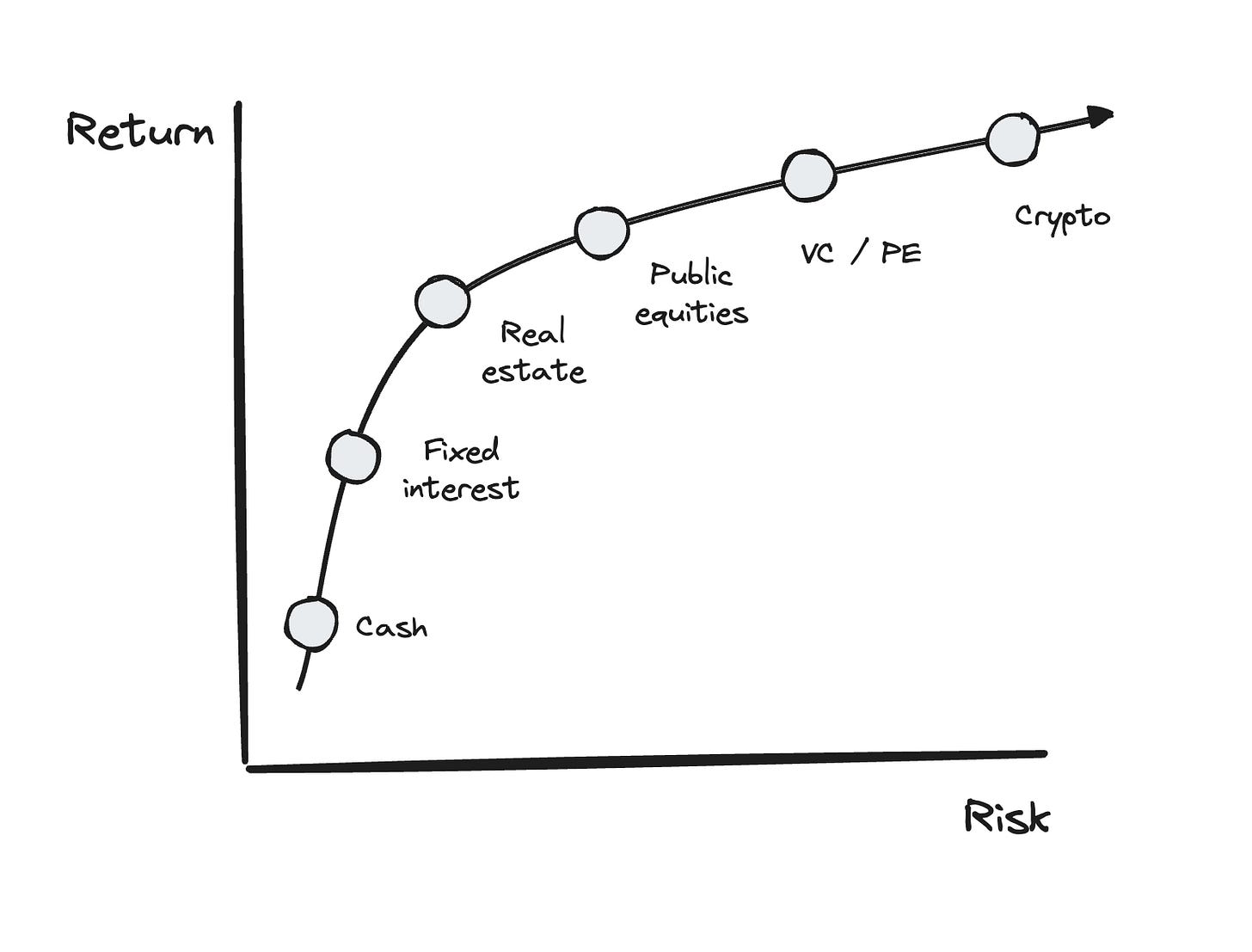

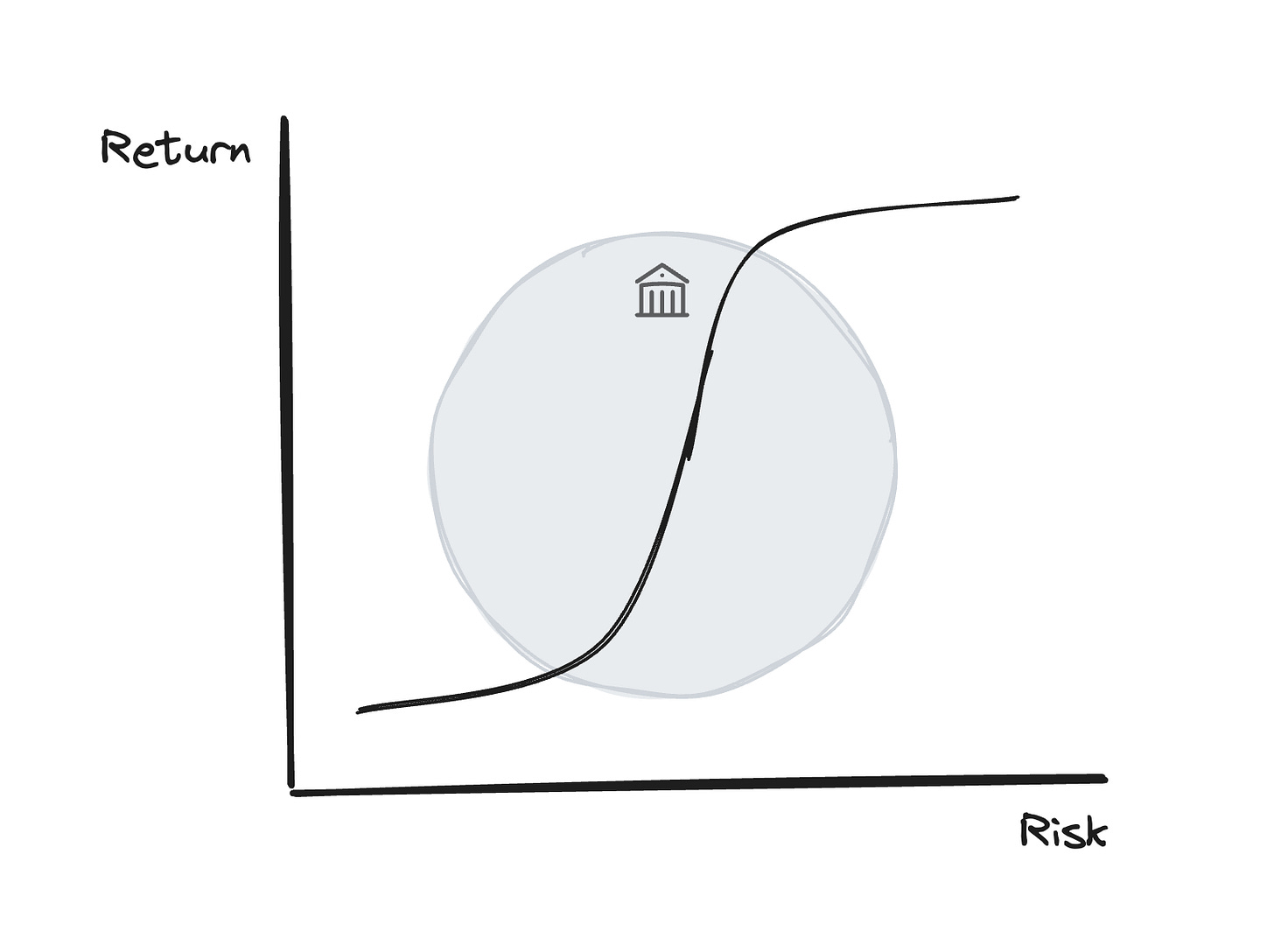

To understand how and why fintechs misunderstand risk, let’s start with the classic risk versus return chart. The more risk you take, the more return you get. For example, across asset classes:

The same trade-off applies to company strategy in fintech, although with a slightly different curve:

The gray circle in the curve’s middle, where you get ever-greater returns for relatively smaller amounts of risk, is dominated by the traditional financial institutions described in the tweet above. That’s the massive, ruthlessly competitive, highly profitable space that fintechs try to break into.

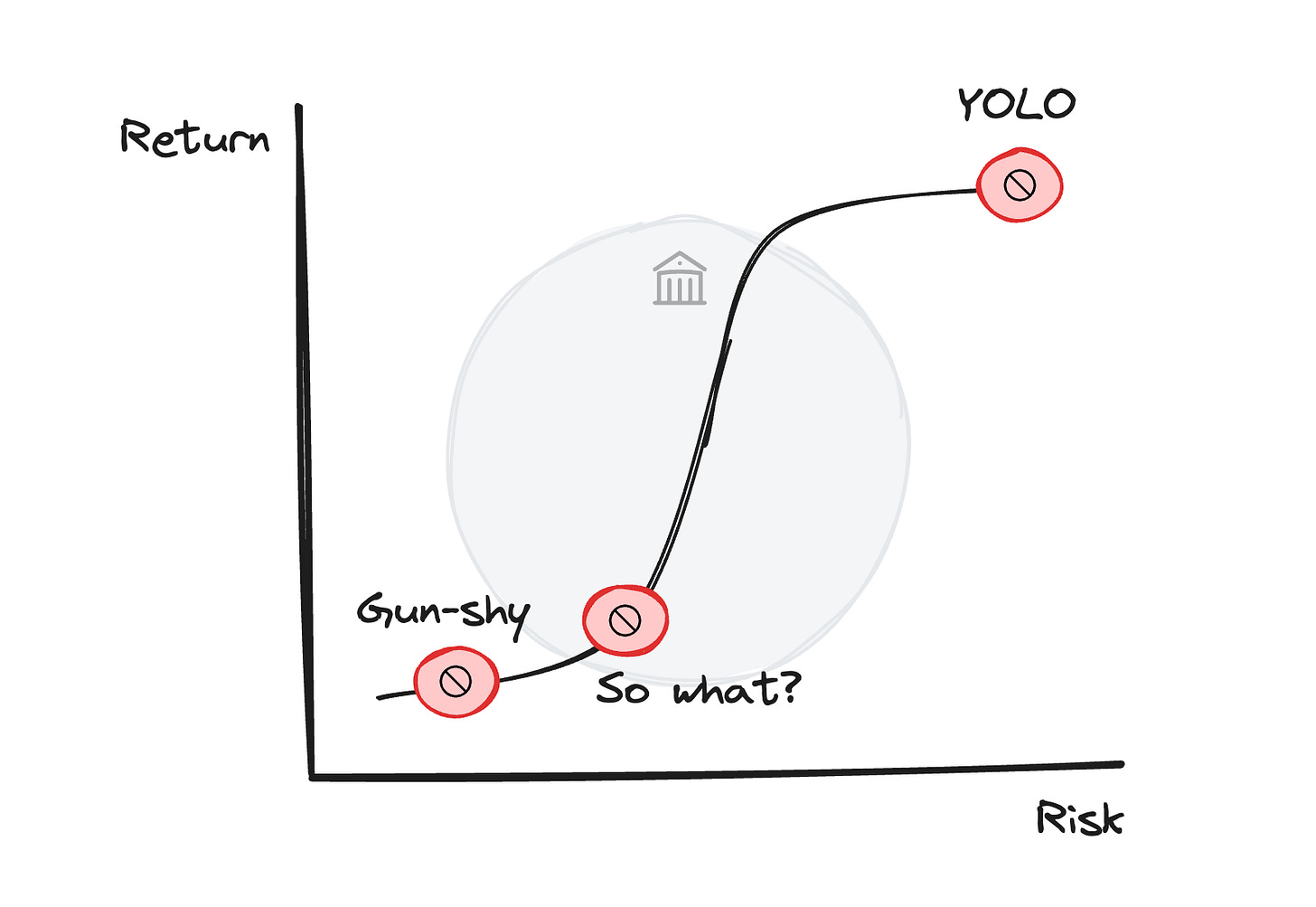

Fintechs that misunderstand or under-appreciate risk fall on three places along the curve, which I call “Gun-shy”, “So what?”, and “YOLO”:

If you remember the motto – “Price and shape risk that others can’t or won’t” – you’ll find that each of these company personas fails to do it in a different way.

(1) “Gun-shy”: They may realize they’re in the risk business, but don’t take enough risk to complete. This is an uncommon profile, but it does happen. To protect against risk, they have very stringent onboarding, or strict underwriting, or narrow risk profiles they’ll accept, or price products above market to compensate for risk. These all lead to a slow demise because the financial sector is so competitive. They won’t lose any money, but they also won’t have enough customers to make much of it, so few will survive.

(2) “So what?”: They realize they’re in the risk business, and take the bare minimum of risk, but are insufficiently differentiated, so they’re indistinguishable from the broader crowded market. Fintechs who don’t understand this but are good at acquisition end up becoming effectively lead gen or referral partners. They’re thin wrappers around traditional financial institutions that ultimately control the UX and economics. Often though not always, these companies appear as thin wrappers around a more competitive company or product, such as the legion of neobanks and card issuers in the late 2010s or the ISOs in the generation before. These businesses may survive, but few will achieve venture scale.

(3) “YOLO”: Whether or not they realize they’re in the risk business, they act as if they’re not. The end of these businesses is best summed by the Hemingway quote: “How did you go bankrupt? Slowly, then quickly.” If you recognize you’re in a risk business, but deliberately loosen controls like onboarding, KYC/B, or underwriting, or deliberately underprice, you can grow quickly for a time, hoping that growth covers all sins and eventually you can “fix” it. It’s easy to grow when you drop prices, play fast and loose with KYC/B, etc. Alternatively, you can just be blind to the risks in the market, grow nicely, and one day realize you’ve been hit by fatal risks.

Notice what’s not mentioned in any of the descriptions above: acquisition strategy and its effectiveness, product quality, etc. None of those matter without an insight into or differentiated approach to risk. As we’ll see below, risk insights often express themselves in marketing or product decisions, but it’s all downstream of that insight or differentiated approach.

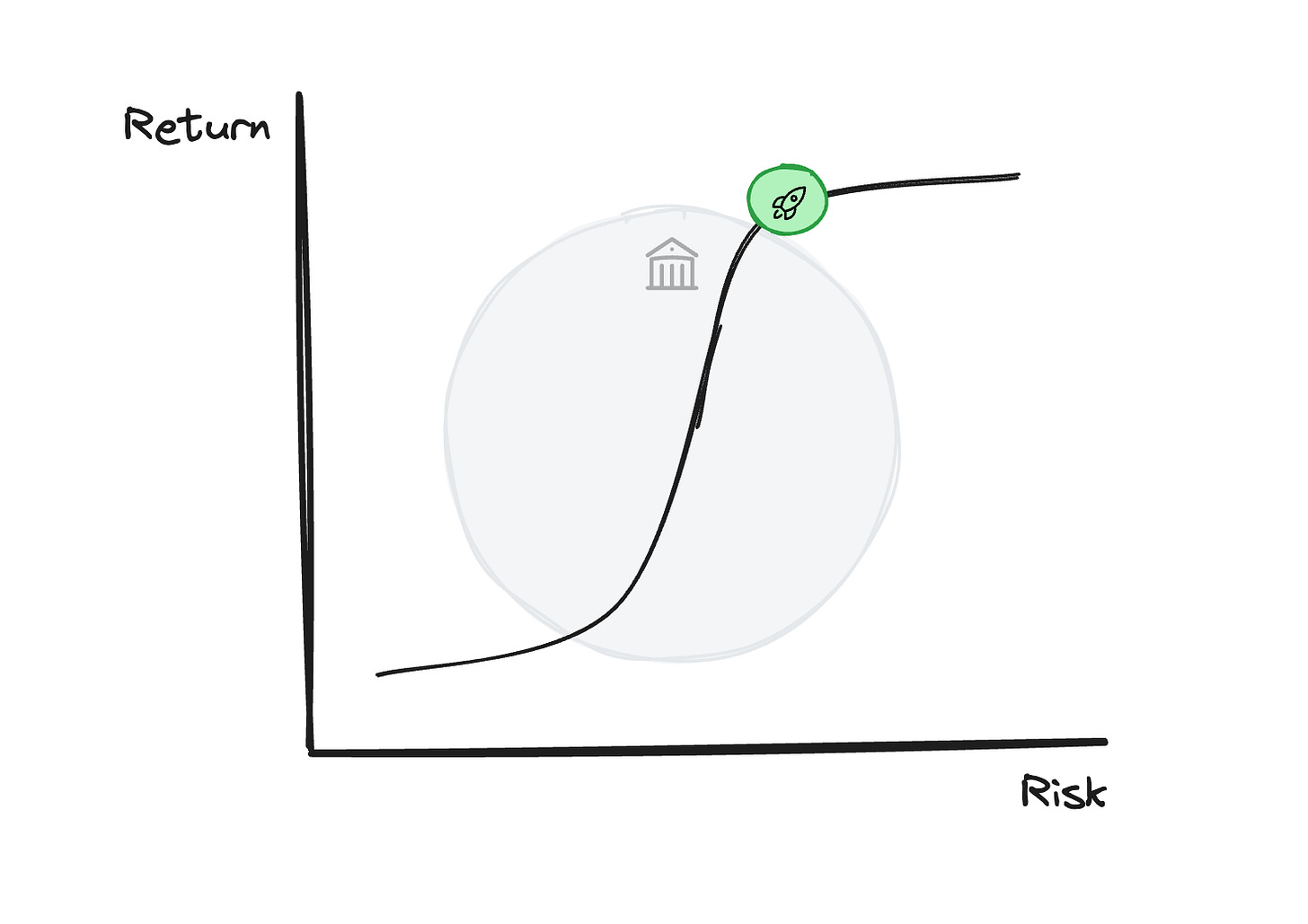

How to actually make money selling money

So how do you make money selling money? You need to care about and build against your risk. To make a lot of money selling money, especially when you’re competing against the world’s “smartest and most ruthless people in a 500 year old industry”, you need to have a novel insight into risk and build a product and company around it.

What does that mean for fintechs? They must have an overarching insight into pricing and shaping risk that others can’t or won’t, and orient most of all of the company (product, marketing, etc) around it. It comes back to the motto for fintechs mentioned earlier: “Price and shape risk that others can’t or won’t”.

This can mean many different things. You can serve customers who seem high risk, but only you can determine that they’re actually not. Or you can serve customers that actually are high risk, but that you can manage and reduce that risk better than others can. Let’s look at a few examples.

BREX

Before Brex, it was difficult for startups to open business bank accounts. This was especially difficult when the startup’s founders weren’t US citizens. While “brand new business plus non-US citizen” may seem like a risky category to traditional financial institutions, in fact these companies were actually lower risk, especially if they had been vetted and funded by accelerators and VCs. Not only were they lower risk than traditional SMBs, but they had higher upside because successful startups go on to raise millions in funding. This gap between perceived and actual risk was recognized and exploited by Brex to get started.

EMBEDDED FINTECH

Another example here is the entire category of embedded financial products, like payments (Rainforest) and lending (Kanmon). I’ve written extensively about the embedded strategy before, but the summary is that embedded financial services can draft off the software platforms they’re embedded into, using their positive selection of users plus existing platform data to acquire and underwrite customers better and cheaper than a traditional financial institution. They can also build vertical or even platform-specific risk models to better price risk.

AFTERPAY

Installment payments, point-of-sale financing, and private-label credit cards had existed for decades before BNPL. Afterpay’s powerful insight was combining the best of several trends (ecommerce adoption, limited traditional credit use among younger consumers, etc) with a deliberate choice of customer segments (fashion and beauty) that reinforced its competitiveness in a space that was somewhere between excruciatingly competitive (consumer credit) and minimal (consumer credit for 18-36 year olds). By focusing on fashion and beauty – where buyers and sellers naturally had a high frequency of lower-value transactions – you could be more flexible in assessing and pricing risk (because the downside the low, especially if 25% was paid upfront) and have leverage in shaping consumer outcomes because you needed to be in good standing to continue using the network as a consumer.

Afterpay is a good example of a series of product choices that may seem odd from the outside, but are deliberate and powerful when viewed through the lens of the risk insight. Risk insights and secrets are, well, secrets. Some publicize them, but most successful companies don’t. And it can be even harder to discern what they are when they’re expressed in non-obvious ways.

I’ve found the deeper and more powerful a risk insight is, the more confusing its manifestations in product and marketing can initially seem. This can be an “ugly” product. Seemingly weird ICP or product messaging. Features that should be there but aren’t, or that seemingly shouldn’t be but are. That’s because the company isn’t oriented around a traditional and observable approach to company building, but around an insight into risk that manifests in non-obvious ways.

This non-obviousness is what makes it so dangerous to copycat and cargo cult successful fintechs, without understanding their risk insight and the series of interlocking product and marketing choices that amplify it. For example, Brex had a genuine insight and arbitrage (seem high risk, actually low risk and high value) in banking, but the multitude of other neobanks that started around the same time did not.

Simply focusing on a specific affinity group or customer segment is insufficient if that selection doesn’t make you better off in risk in some way. The same applies for the multitude of companies that tried to do BNPL for different sectors. They copied what they could see superficially of Afterpay’s company and strategy, without understanding the foundational importance of customer selection and risk orientation.

Startups are an exhilarating but brutal game. Fintech founders play that game on hard mode because they’re competing against large, ruthless, and efficient incumbents who generally know what they’re doing and have been playing the game for decades. To win any game, you need to know the rules and where you have an edge. Successful companies require a million things to go right, a lot of luck, and a ton of hard work, but in fintech, they also require a deliberate appreciation of and insight into risk.