Why VC and software have PE envy

Gone are the days of minority investments in high-growth, asset-light, software-led startups. Why do so many VCs and VC-backed companies seem to be acting like PE firms these days?

Imagine you’re the world’s most entrepreneurial dentist, the Mark Zuckerberg of molars. You’re great at cleaning teeth, but you’re also great at running a practice. You have your own playbook for the dental business.

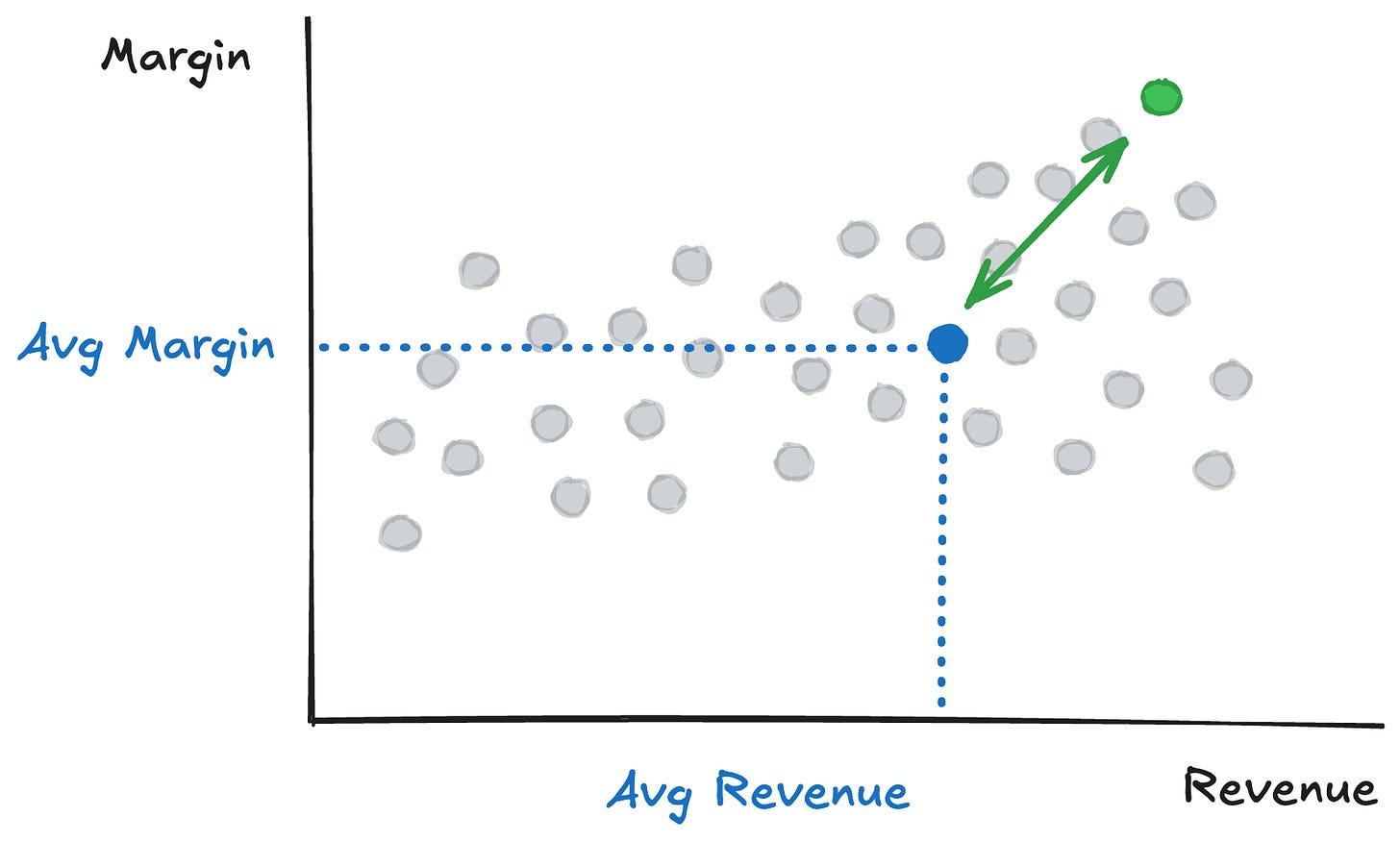

Thanks to your playbook, your practice is larger and more profitable than the market average. You’ve surveyed your dentist friends. You’ve learned that you’re the best at acquiring patients, running your back office, configuring your CRM to minimize cancellations, and getting paid quickly. But you aren’t satisfied with cleaning teeth all day. You want to build a dental empire. The gap between the average business and what’s possible with your playbook is your opportunity.

Software engineering vs. financial engineering

How do you start your empire? Until recently, there were two broad and distinct paths: private equity (PE) and venture capital (VC).

In the PE model, you’d raise money to acquire a controlling stake in one or more practices. Then you would have full control to implement your playbook and manage those practices day-to-day.

In the VC model for B2B software, you’d raise money to start a company that builds software that codifies your playbook for any practice to implement. Maybe it’s a suite of CRM, scheduling, and billing tools, with opinionated workflows and design choices specifically for dental practices. You wouldn’t own or manage any practices directly, but your software would help them run better.

Both models start with the same principles: (1) the average company in a given vertical isn’t run as effectively as it could be, and (2) you have the insights and playbooks to run the average company more effectively. You believe you can close the gap between the blue and green dots, and get paid handsomely for it:

However, the PE and VC models take very different approaches to point #2. The tradeoffs of each model are most obvious in their approaches to control, concentration, and value capture.

The PE model is high control, high concentration, and high value capture. It says, “This specific business can be run better, and so it’s likely undervalued. I’m going to buy and run it, applying my playbook. As the business grows and becomes more efficient, it will become more valuable. I’ll benefit from the increased equity value.”

The VC model (at least within B2B software) is low control, low concentration, low value capture relative to an individual business. It says “There are lots of businesses in this market, and most of them could be run better. I’m going to build software that helps them do that. I’ll charge a small fee, but will sell it to many businesses.”

The PE and VC models are extreme ends of a spectrum, rather than distinct models. PE and VC firms are both in the business of generating returns for their investors. They take capital, combine it with their belief in the superiority of their playbook, and then implement their strategies and playbooks in a given vertical. This may involve buying businesses or building tools to enhance their performance, generating profits, and returning the profits to their investors.

Until recently, you’d be forgiven for thinking PE and VC are effectively distinct entities. However, headlines like these are making it more apparent that they’re just a spectrum of strategies and that there’s a lot of white space in between them:

Why are VCs (and the companies they fund) adopting PE-like strategies? Let’s explore.

Pushing toward and pulling from the messy middle

In seeking outsized returns, VCs and venture-funded startups are venturing beyond their previously narrowly defined model. They’re getting more creative and aggressive in exploring the messy middle, the whitespace between the previously distinct PE and VC ends of the spectrum.

Several factors are behind this move towards the messy middle. Some are pushes from the traditional VC model: the classic, almost boutique approach of minority investments in asset-light, high-growth, all-or-nothing, power-law-seeking, software-first-and-only startups. As this model gets more competitive, smart founders and investors realize they must try something different. At the same time, several powerful factors are pulling toward these new models: new technologies and business models seem to enable venture-like returns from traditionally non-venture-type businesses.

The push side is well-documented: the traditional VC asset class has become saturated, especially in B2B SaaS. Nearly a trillion dollars have flowed into the venture industry in the last decade. This has led to a proliferation of companies serving every vertical and every niche. Some market maps are so crowded that you need a microscope to make out a single logo:

At the same time, AI promises to further reduce the cost of software development. That isn’t to say that the B2B SaaS market is going to zero, or that there won’t be another generational B2B SaaS business. But the noise and saturation make it harder for these companies to grow quickly while retaining customers and high margins. There aren’t many land grab opportunities in pure SaaS like there were in the 2010s.

Even for companies with great products, it’s getting harder to sell to businesses with SaaS fatigue. To return to the original dental example: suppose you (the entrepreneurial dentist) build the best vertical software for dental practices. Your target customers are already inundated with such pitches. The same is true if you’re pitching the most well-oiled acquisition strategy for underperforming practices. It’s hard to sell them a genuinely better product, and it’s also hard to convince them to sell their businesses.

That brings us to the pull factors. What makes the non-pure-software approach so attractive? First, new tech and business models enable startups to monetize more than just software subscriptions. I talked about this in “Invisible asymptotes in vertical software”. Products like embedded payments with Rainforest* or embedded marketing with Reach* allow software companies to capture a variable portion of their customers’ success, upside that grows as their customers grow, and not just a fixed fee for software.

Another is the rise of AI as a credible substitute for certain types of work. This has two direct effects:

First, it allows significant costs to be taken out of a business and/or for labor to be added to places where it previously wasn’t economical. For example, an accounting firm that previously needed a large back office team for mundane, repetitive tasks can offload more of that to AI and reduce headcount. A small field services business can now use voice agents to answer the phone at a fraction of the cost of a full-time employee.

Second, AI allows companies to implement a broader, more consistent, and more scalable version of playbooks. If PE involves implementing playbooks for teams to follow, while VC involves building software that encodes playbooks into workflows and data models for teams to follow — both are vulnerable to human error. In both cases, the people involved need to actually follow and implement the playbooks. AI takes that out of human hands.

So, VC funds and venture-backed companies can and must explore strategies in the messy middle. They both (1) must move away from old and less effective models, and (2) can adopt new models with higher expected returns. That’s why seemingly unconventional company structures have emerged.

The yin and yang of code and capital

To improve businesses and generate returns, the VC model uses code as its primary source of leverage, while the PE model uses capital. The new models mix code and capital in unique ways to achieve the same result: improve how a set of businesses operates, then harvest upside. The latest mixtures of code and capital allow investors and entrepreneurs to work with more businesses. They also make it possible to create and capture more value than was previously possible in a pure VC or PE model.

The new models seem to fall into three categories: the crown jewel, the roll up, and business-in-a-box.

In the crown jewel model, a VC firm or VC-funded company acquires a one-off, large, strategic, and non-tech asset. The crown jewel might be a hospital or health system, a professional service firm in law or accounting, a call center or BPO, or a parking lot operator. The acquirer doesn’t simply acquire and run a business marginally better (as in traditional PE). The acquirer may already have a proprietary tech stack or strategy that it’s applying to the crown jewel asset. Or the acquirer may build such technology as it operates the new business, with the crown jewel asset as its ideal and captive first customer. Under this model, the acquirer applies proprietary tech to an already at-scale business where it will have the greatest and fastest ROI. Crown jewel examples include the AI-powered parking software company Metropolis acquiring a century-old, publicly-listed parking lot operator SP Plus for $1.5 billion, or General Catalyst acquiring a large healthcare system in Ohio for $500 million.

In a venture roll-up, a company acquires multiple non-tech assets and then applies its proprietary technology and strategies. Think of a roll-up in contrast with the opportunistic, often one-off, and strategic M&A of the crown jewel model. In the venture roll-up model, the M&A is continual and applied to multiple businesses. Traditional PE often involves a low-tech roll-up approach. The venture roll-up model differs from the PE roll-up because it involves applying a full stack of proprietary, purpose-built software for that vertical. The venture roll-up may also build in-house technology to assist and scale the M&A process, such as proprietary data and underwriting to identify, underwrite, and value the best acquisition targets. Examples include Cabana, Pipe Dream, and Long Lake in field services, as well as OLarry and Multiplier in professional services.

In the last model, business-in-a-box, the company actually helps create and start new businesses in a vertical. Like the roll-up model, it brings proprietary technology and works with multiple end businesses in parallel. But it creates these businesses rather than acquires them. It can create businesses under unique individual brands (business-in-a-box) or under a common brand (modern franchising). These can include purely digital services offered at least partly through a managed marketplace. Examples include Fora for travel agents or Headway for therapists, as well as brick-and-mortar businesses, such as Moxie for med spas. Sam Gerstenzang, the founder of Moxie and Boulton & Watt, is the expert on the model and wrote a great piece on which markets are most amenable to it.

These models are evolving quickly and aren’t mutually exclusive. For example, biz-in-a-box vendors may execute some opportunistic roll-ups or vice versa. Similarly, incumbent vertical software companies may begin adopting these new models. To return to the PG tweet above, if a vertical software provider finds its market or margins tapped by just selling software and services, it may be compelled to start operating businesses in their verticals. Alongside the list of products vertical SaaS companies offer, such as CRM and payments, it’s increasingly common to see an option to “Start your business with us” or even “Sell your business to us.” For example, Slice (“Start your pizzeria”) or MoeGo Care. This creates some interesting territory to navigate — including the potential for channel conflict and competing with existing customers.

The biggest companies are built and the best investments made when things are in flux, when generally accepted models have been exhausted, but no obvious replacement has risen. That flux is happening in VC and PE. The classic VC/PE investment model, as well as the traditional strategy of VC-backed, SaaS-centric, B2B software companies, is approaching a saturation point. It’s still early as funds and companies explore new combinations of code and capital, of software and financial engineering, in this messy middle. Interestingly, it isn’t just a game for new funds or companies. Some of the earliest examples of this trend are established investors (e.g., General Catalyst / Summa) and software companies (e.g., Metropolis / SP Plus). But the model is evolving, and there will be many new opportunities to build generational companies by creatively mixing code and capital.

My name is Matt Brown. I’m a partner at Matrix, where I invest in and help early-stage fintech and vertical software startups. Matrix is an early-stage VC that leads pre-seed to Series As from an $800M fund across AI, developer tools and infra, fintech, B2B software, healthcare, and more. If you're building something interesting in fintech or vertical software, I'd love to chat: mb@matrix.vc