Cross-border payments in ~1,000 words

A gentle introduction to correspondent banking, money transmission, payment aggregation, and stablecoins, as well as cross-border payment business models and product strategies.

This is the fourth installment of the “X in 1,000 words” series, following interchange, payfacs, and real-time payments. These are intended to introduce critical but mis- or under-understood topics to people working or interested in fintech. It’s not an exhaustive guide, but the gentle introduction and overview I wish I had earlier. Questions and feedback are always welcome. You can learn more about and contact me here.

"Cross-border payments" are payments made between parties in different countries. While the concept is straightforward, the systems that move >$45 trillion annually across borders are anything but. That’s because cross-border payments (XBP) must account for things domestic payments take for granted.

Say I want to send $100 USD to a friend in Japan. Those funds need to somehow move between two banks that may not have a direct relationship with one another across different payment rails and regulatory regimes and eventually land as Japanese Yen (JPY) in an account around the world.

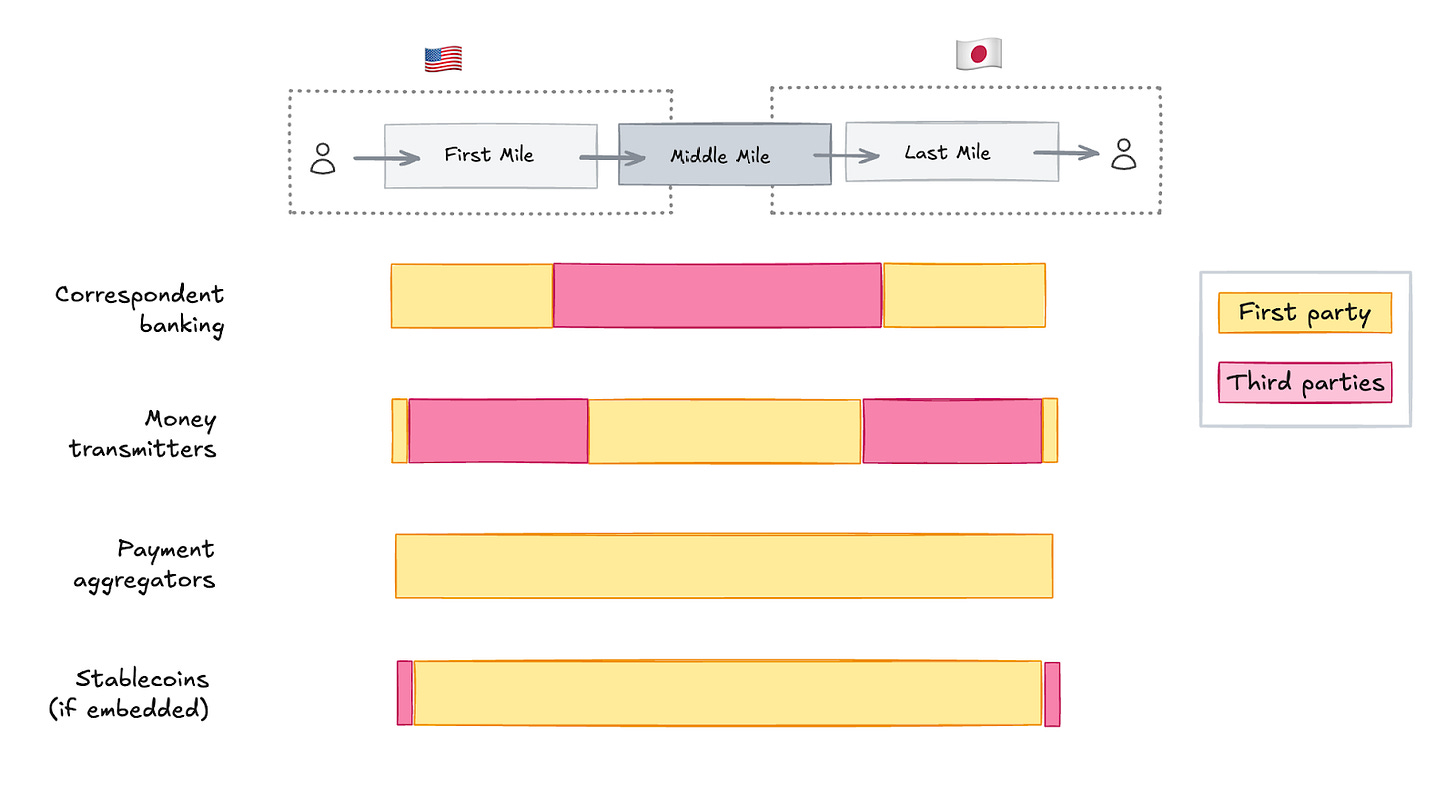

The various solutions to this involve two common parts: (1) acquiring and supporting local users on both ends of the transaction, including first/last mile of money movement and local regulatory compliance, and (2) the “middle mile” of moving money or value across borders, converting currencies, and managing FX and liquidity risks:

This note covers four XBP methods: correspondent banking, money transmission, payment aggregation, and stablecoins. I’ll discuss the trade-offs inherent in each solution, as well as the factors that affect the product and business strategies of XBP companies.

Correspondent banking

Correspondent banking is a long-standing and still dominant XBP method. It describes how banks establish arrangements and accounts with banks in other countries and then work together to provide services like XBP. For example, an American bank like Chase will maintain an account in a Japanese bank like SMBC funded with JPY.1 Banks use SWIFT to coordinate payments. SWIFT isn’t a payment rail but a secure messaging system. The money movement is accomplished by netting the local accounts and/or with settlement systems like CHIPS (US) or TARGET2 (Europe).

Say I wanted to send $100 to that Japanese friend. If Chase and SMBC have an existing relationship, they’d coordinate using SWIFT, net the JPY from Chase’s account at SMBC, and credit it to the recipient’s JPY account:

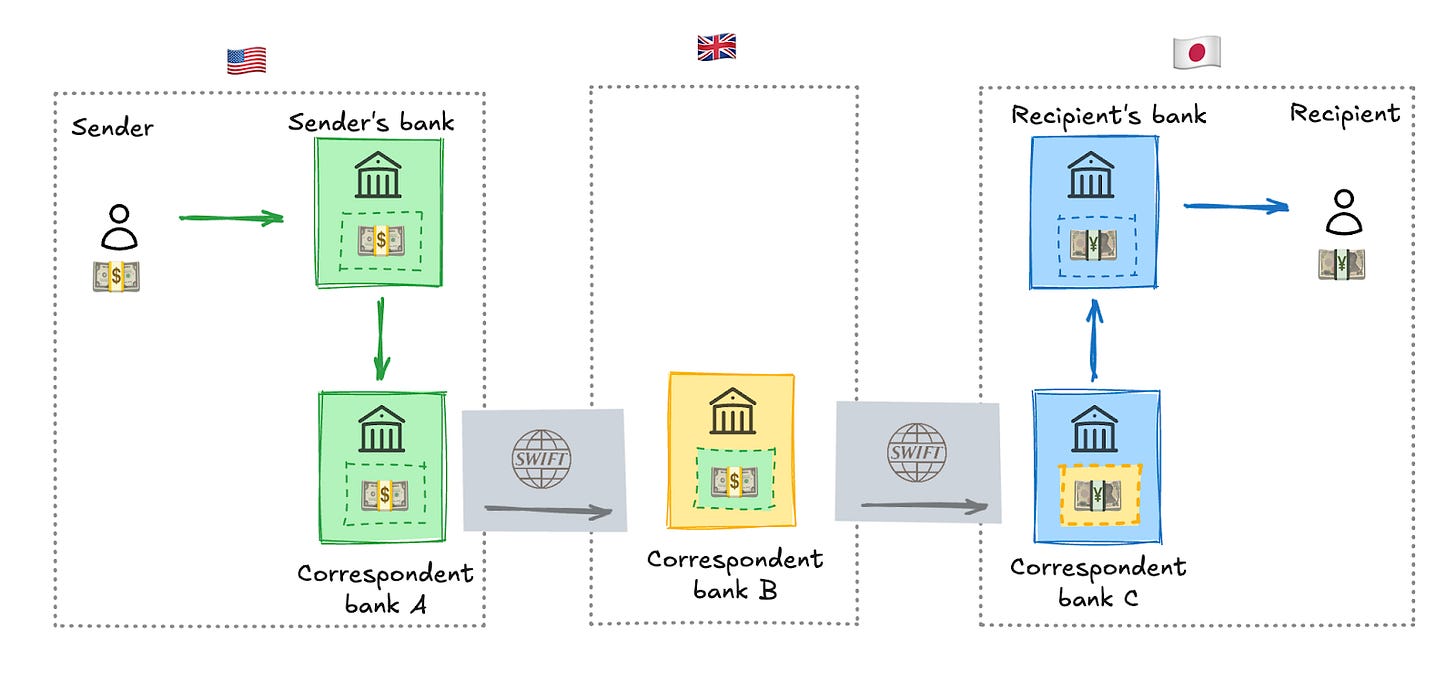

If the sender and recipient’s banks don’t have a pre-existing relationship, they’d use correspondent banks as intermediaries. In this case, Correspondent Bank A has the JPY nostro account with Correspondent Bank B:

Correspondent banking can involve multiple intermediaries, including in third countries, to complete transfers:

The benefit of this method is wide coverage: the network can eventually connect almost any two banks. However, this comes at the expense of speed and cost, as each intermediary takes time and a fee to process the funds through the network.

Money transmitters

Money transmitters (MTs) such as Western Union and Moneygram are another long-standing and popular XBP method. They’re popular among the un/underbanked since the sender and/or receiver can transact in cash. MTs operate a global network of agents – physical storefronts such as conscience stores or currency exchange stalls – that offer MT services. Senders deposit cash with an agent and leave instructions for who can retrieve it elsewhere on the MT’s network.

For example, say I deposit $100 at a Western Union location in San Francisco and list my Japanese friend as the recipient. The agent verifies my request and then sends the funds to Western Union.

Western Union credits them to my friend in Japan and nets the funds between its USD and JPY accounts minus a fee. My friend can then pick up the equivalent in JPY at a Japanese Western Union agent by showing their ID or a confirmation code:

Correspondent banking and money transmitters are often critiqued for being slow and expensive. This cost and slowness are the downsides of their broad geographic coverage, resulting from their reliance on intermediaries. Because many MT users lack formal banking, an agent network is necessary for first/last mile distribution. In contrast, the lack of 1:1 global banking connectivity necessitates the correspondent banking network for the middle mile. Now let’s discuss two newer XBP models, which use technology to minimize intermediaries.

Payment aggregation

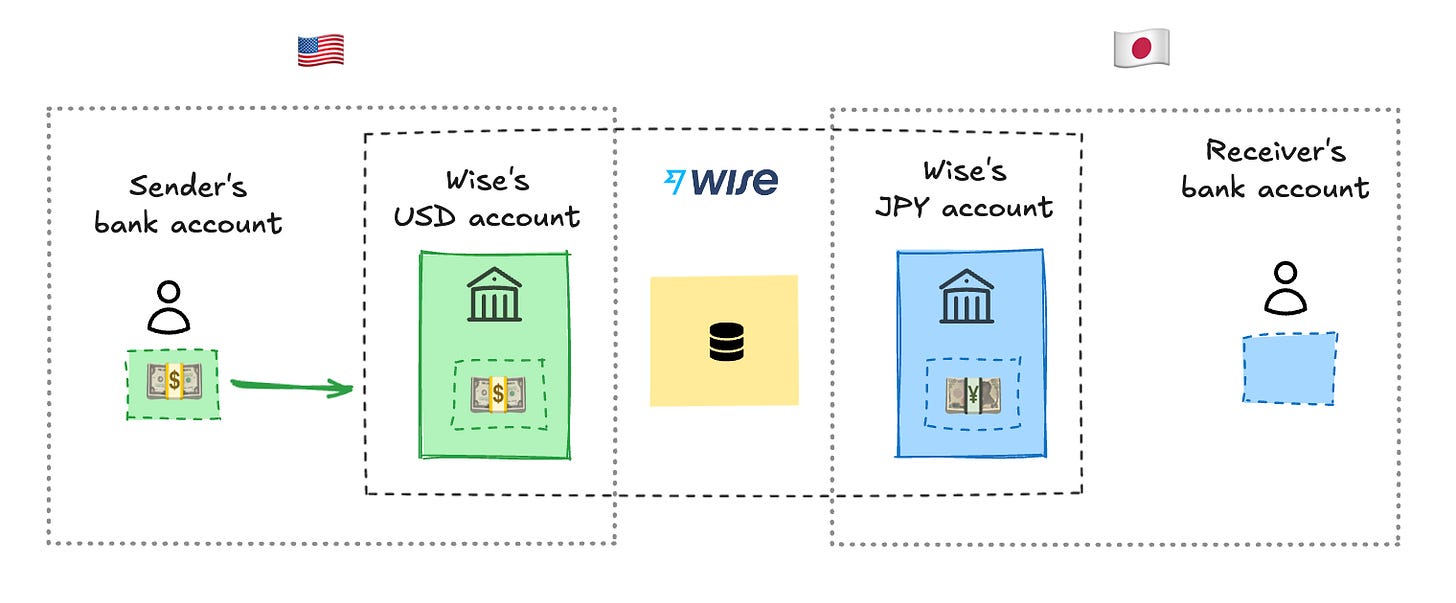

Payment aggregators like Wise can be considered digital-first money transmitters, with apps instead of agent networks. These companies maintain bank accounts in the countries they support, pre-funded with local currency, and the infrastructure to pay in from and out to local users on each end. The actual “cross border” transactions are often internal net transfers, similar to correspondent banking, but the fintech orchestrates the transaction.

Let’s return to the example above, but use Wise to send money to Japan. Initiating the transfer, I’ll send $100 from my bank account to Wise’s USD account:

Wise will then transfer the equivalent amount from its JPY account in Japan to my friend’s SMBC account. No USD leaves the US and no JPY enters Japan.

This is faster and cheaper than correspondent banking and money transmitters because there are fewer intermediaries. Because Wise is the intermediary, it has more control over everything from the UX to the costs. This benefit does not come easily though. Beyond maintaining the local accounts, Wise must acquire and support users, comply with local regulations like KYC, manage liquidity and FX risk across countries, and more. Wise users are also limited to countries where Wise has established on/off ramps.

Stablecoins

The newest kid on the XBP block is the stablecoin, which offers several improvements on all other XBP methods. A stablecoin is a digital currency backed 1:1 by fiat currency like USD, so its value is constant, and it’s tradable instantly and globally. Since the blockchain and exchanges never close, stablecoins can be converted almost instantly to/from fiat. When combined with burgeoning 24/7 fiat real-time payment networks, stablecoins enable near-instant fiat > stablecoin > fiat transactions.

Taking the USD to JPY example again: once the sender initiates a transfer via Bridge or a platform that’s integrated it, USD moves over local fiat rails to Bridge’s local USD account:

Bridge then exchanges the USD for a stablecoin such as Tether (USDT), and transfers it to a wallet linked to its bank account in the recipient’s country. The USDT is then converted to JPY in Bridge’s local Japanese bank account and moved over local rails to the recipient’s account:

Like payment aggregators, stablecoin infra providers must maintain local accounts, follow local regulations and compliance, such as KYC/B senders and recipients, and more.

Cost, speed, coverage: the XBP trade-off

All XBP systems must solve the core problem that a sender and recipient, as well as their respective banks, may not be directly connected. The solutions to this problem create trade-offs in speed, cost, and coverage of supported countries/currencies.

Correspondent banking and money transmitters were pioneered in the pre-digital era2, so their models use networks of intermediaries in different ways to solve the same problem. They generally optimize for coverage at the expense of speed/cost. Payment aggregators and stablecoins use technology (e.g., better onboarding and servicing via mobile apps, faster/cheaper pay in/out via emerging RTP rails) to reduce or eliminate intermediaries:

Interestingly, some new players offer embedded models, either as a pure play (e.g., Airwallex, Nium, Bridge) or as a complement to their existing direct business (e.g., Wise Platform).

XBP economics and product strategy

Beyond the mechanics of how money moves across borders, it’s important to understand how factors like sender/recipient and country/currency mix determine the strategy and economics of XBP companies.

The sender/recipient mix (C2C, B2C, C2B, B2B) determines distribution strategy, regulatory and compliance burden, product adjacencies, etc. Because businesses generally send and receive more payments more frequently than consumers, they have more pricing leverage and see lower take rates than mixes involving consumers. For example, Remitly (C2C) has a gross take rate of >200 bps versus Corpay (B2B)’s <60 bps.

The corridor is another important determinant of take rate. Generally corridors with larger volumes, more stable currencies, more balanced flows, modern banking infrastructures, and complementary regulatory regimes are more competitive and therefore have lower take rates. Inversely, there’s typically less competition and higher take rates with more volatile currencies, unbalanced and low/inconsistent flows, and antiquated financial infra. The take rate is up to 25x greater for the least competitive corridors.

Many XBP companies follow the general fintech trend of complementing low-margin transactional revenue with other complementary financial products and/or higher-margin software products. For example, Wise offers interest-bearing deposit accounts while Flywire offers vertical software for its key industries, like education and healthcare. Embedding for distribution is another popular strategy, with companies that were initially direct-to-consumer offering products like Wise’s Platform and Airwallex’s embedded solution.

That’s XBP in ~1,000 words! If you’re building in this space, email me: mb at matrix.vc