Payfac in 1,000 words

Payfac is the model behind fintech’s biggest successes, from Stripe and Square to Shopify, Uber, and more. It's a critical but often misunderstood topic, so here's an overview in 1,000 words.

Many fintech topics are daunting. When I started as a founder, grokking things like interchange or KYC/KYB was an uphill battle. This “X in 1,000 words” series is my attempt to make fintech more accessible by writing the guides I wish I had starting out. If you find these helpful—subscribe and let me know what you’d like to see next: mb at matrix dot vc

We take card payments for granted because they’re so commonplace. It feels like ordinary magic to use a slice of plastic in your pocket to move money from your account to any merchant—online or offline, Fortune 500 company to roadside seller, anywhere around the world.

“Interchange in 1,000 words” covered how money moves between buyers and sellers, through a complex web of issuers, acquirers, and other intermediaries. Card schemes or networks, like Visa and Mastercard, are at the center of this:

Payments is a network effect business and benefits from cross-side network effects.1 Every payment method has buyers who use it and sellers who accept it. The more sellers accepting a payment method, the buyers value that method. The more buyers that adopt it, the more valuable it is to sellers, and so on.

The more nodes (cardholders and merchants) the card network has, the more valuable it is. So it’s critical that networks and acquirers add merchants to increase card acceptance.

However, offering card acceptance is expensive and complex. There’s the costs of marketing and selling to merchants, underwriting and managing risk, support and servicing, etc. That’s why networks rely on…

Merchant Acquirers and ISOs

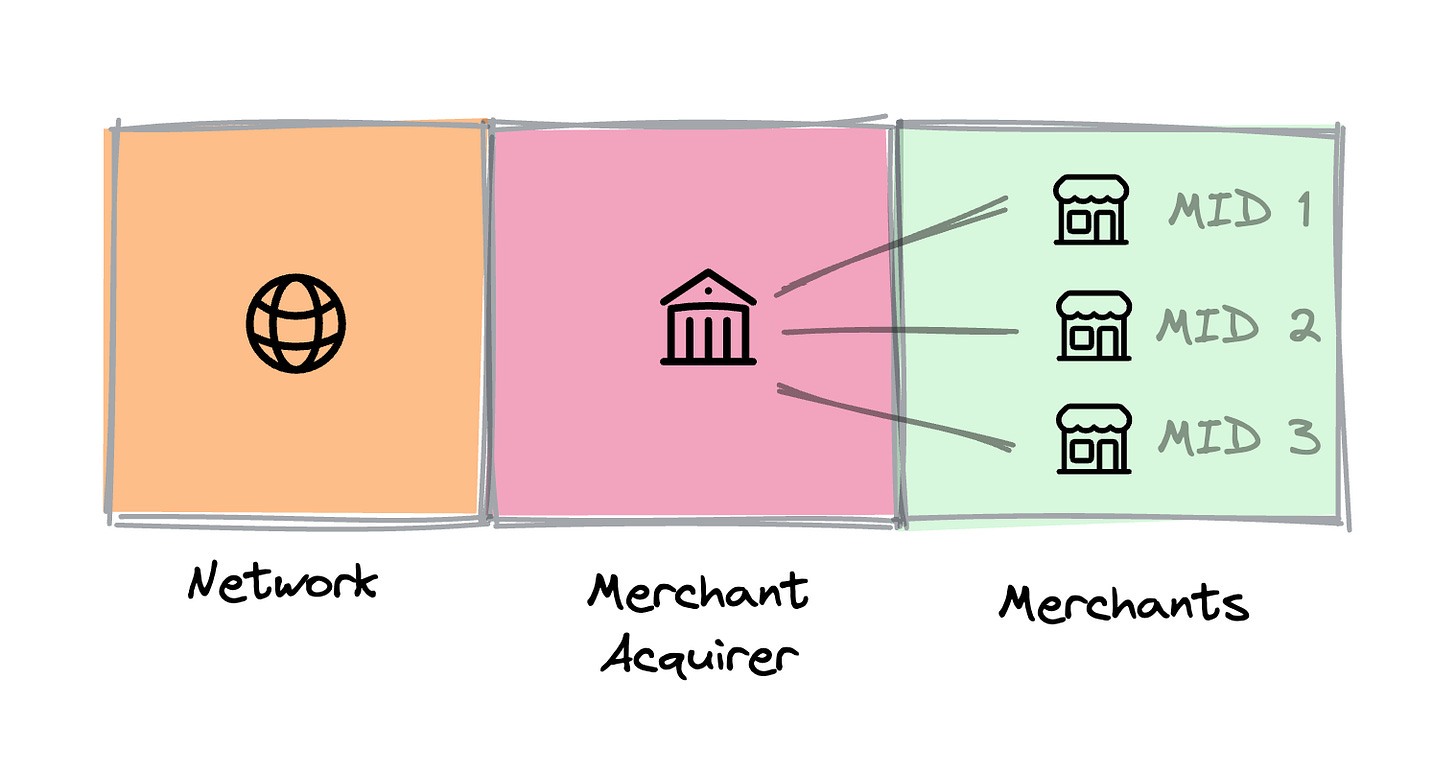

The original card payments model was for Merchant Acquirers (MA), like Wells Fargo or Chase Paymentech, to offer card hardware and services to merchants. MAs give merchants a Merchant Account and Merchant ID (MID), which are unique to that merchant and help approve transactions, route funds, etc. Merchants can have different MIDs, but generally each MID applies to a single merchant. The MA generally monetizes transaction fees, which it splits with the network and issuer.

While some merchants work directly with MAs, others are too small or don’t have an existing relationship with an MA. Many MAs will license third parties called Independent Sales Organizations (ISO) (like Global Payments and Elavon) to sell acquiring services on their behalf. ISOs generally make money by selling or leasing card acceptance hardware, offering consulting and other services, and fees from the MA.

This allows the MA to outsource functions like sales and support while activating more merchants than they could on their own. Under the ISO model, the MA generally does the underwriting and takes the risk, although different ISOs have varying levels of involvement here.

Although more merchants are generally better to networks, MAs, and ISOs, there are practical limitations. Card acceptance hardware can be prohibitively expensive for some merchants. Many of the functions needed for an MA and ISO to offer card acceptance are still too expensive to offer directly to many merchants. Especially in the pre- and early internet era, this kept fixed costs high. So MAs and ISOs focused on larger, more established, and less risky merchants, and so excluded many smaller, newer, or riskier merchants. That was until ~2008…

Payment Facilitators

Like many tech revolutions, it took new platforms to bring deflationary pressure and innovation to the market. For payments circa 2008, that was mobile and cloud computing. The then-new iPhone provided a cheap replacement for expensive and specialized card terminals. Square was early to this with its headphone port reader (originally patterned on an acorn). Another startup called “/dev/payments” (later Stripe) allowed developers to accept payments with a few lines of code.

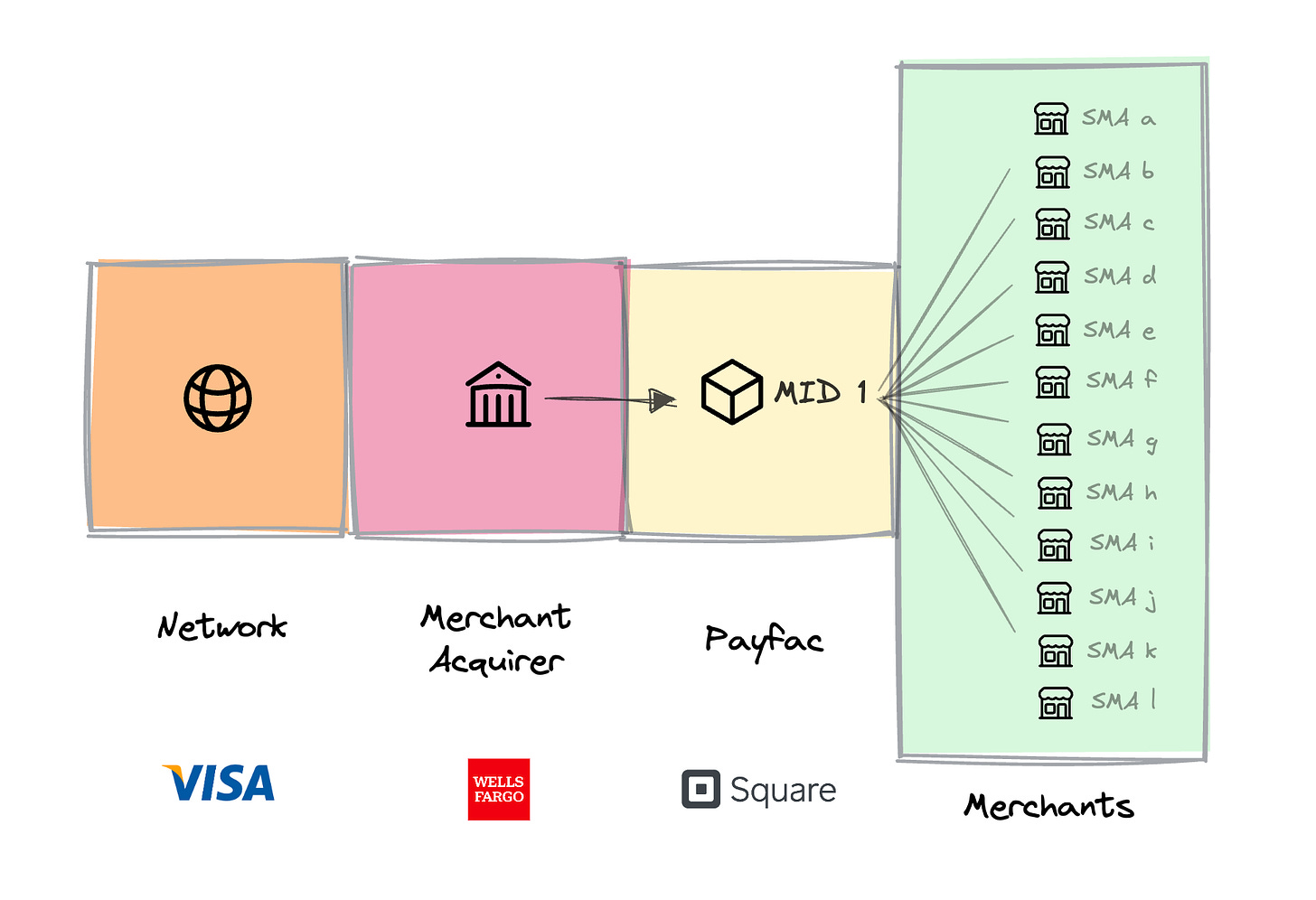

These companies targeted underserved merchants (Square’s farmers market sellers, Stripe’s small software companies) by eliminating the need for expensive, specialized hardware and services. But MAs still required each merchant to have a unique MID. The critical innovation of these new companies, which were eventually called payment facilitators (payfacs), was to have one or more MIDs themselves and aggregate merchants under those MIDs with Sub-Merchant Accounts (SMAs).

While ISOs generally let MAs handle merchant underwriting and risk, payfacs took more responsibility for this from MAs in exchange for greater flexibility and economics. It took time, but networks and MAs eventually got comfortable with the payfacs having robust enough compliance and risk controls to offload some of that responsibility.

Networks and MAs were incentivized to accommodate this model because of cross-side network effects. Payfacs dramatically expanded the nodes in the card payment network. The more merchants that accepted cards, the more valuable the card network was to cardholders, and the more funds would flow through it. The networks delegated some control, risk, and flexibility to payfacs in exchange for an expanded network, network value, and payment volume.

Payfacs monetized the payment flow directly and used their relationship with merchants to cross sell products and services. Most mature payfacs today offer a range of complementary products, from various hardware options (e.g., Toast’s various hardware products) to payments-adjacent software (e.g., Stripe’s Tax and Billing) to straightforward B2B software (e.g., Square’s Marketing or Payroll). As the success of this model became known, it led to a further evolution…

Payfac-as-a-Service

The growth of the SaaS, e-commerce, and other software markets in the 2010s led many inside those businesses to realize how strategic and lucrative embedded payments could be. Platforms serving merchants, like Shopify in e-commerce or Mindbody in vertical SaaS, are called Independent Software Vendors (ISV). Many considered becoming payfacs themselves, but saw it as too burdensome for a non-fintech company.

This led to the Payfac-as-a-Service (PFaaS) model: existing payfacs allowed ISVs to offer payment acceptance to their end users, with the payfac managing much of the onboarding, risk, money movement, and more for the ISV. For example, Shopify (ISV), offers Shopify Payments, which is actually powered by Stripe (a payfac that offers PFaaS). Stripe pioneered this model, but it’s being enhanced and scaled successfully by newcomers like Rainforest.

While ISVs share payment revenue with the PFaaS, the ISV will often monetize multiple services, like a SaaS offering or other financial products. Shopify, for example, charges all merchants a subscription fee, but earns more than half of its revenue from financial services like payments.

This shows the power of the PFaaS model. Wells Fargo (MA) or Stripe (PFaaS) are unlikely to have individually the resources or expertise to serve millions of e-commerce merchants. But by partnering with an ISV like Shopify, they can provide card payments to those merchants while eliminating the need to acquire them and minimizing the burden of serving them directly. Cardholders have more places to use cards, merchants can accept payments easily, and the ISV, payfac, MA, and network all see greater transaction volume and revenue. The power of network effects in action.

The future of payments

The payfac and PFaaS trends exemplify the effect of software on financial services and other industries: it lowers fixed costs and enables new distribution channels, pushing the service closer to the end user in a more integrated, user friendly, and cost effective way.

These trends also reiterate how much payments is fundamentally a network effect business. More acceptance = more cardholders = more payment volume = more network value. The broader trend from ISOs to payfacs to PFaaS is one of networks and MAs delegating control and responsibility in exchange for more merchants, more payment volume, and a more valuable network.

While the PF and PFaaS model isn’t new, it’s still growing fast, with software-led and e-commerce channels quickly eating into traditional ones:

The model’s still a fraction of its ultimate potential. There’s lots to build around payments and other embedded financial services, as well as the vertical ERPs and dark software companies capturing and growing markets with them.

My name is Matt Brown. I’m a partner at Matrix, where I invest in and help early-stage fintech and vertical software startups. Matrix is an early-stage VC that leads pre-seed to Series As from an $800M fund across AI, developer tools and infra, fintech, B2B software, healthcare, and more. If you're building something interesting in fintech or vertical software, I'd love to chat: mb@matrix.vc

These are cross-side network effects versus regular network effects because there are two types of users (buyers and sellers). Pure network effects and things like Metcalfe’s Law apply when network nodes are homogenous (e.g., each telephone line makes the telephone network more valuable because it can both receive and make calls). Cross-side network effects, which appear in marketplaces like eBay or Uber, are equally powerful but are trickier because they must be balanced. An overabundance of supply or demand could be harmful (e.g., too many Uber riders and not enough drivers results in long wait times and surge pricing).